A core taken from a peat bog offers a form of time travel, letting us think of landscape as layers of its former self.

On April 22, 2016 (Earth Day), a group gathered at Kirkconnell Flow for a demonstration of peat-core sampling by Dr Lauren Parry – lecturer in Environmental Sustainability at the University of Glasgow.

Kirkconnell Flow is one of the best preserved raised bogs around Dumfries, thanks to an EU funded peatland restoration project. Lauren explained that this kind of bog plays a really important role in locking up carbon, which has been laid down over thousands of years by Sphagnum moss. For this reason, preserving peat bogs plays a crucial role in mitigating climate change. Peat bogs store carbon in a different way than forests. One way of understanding this is to think of peat bogs as being like a long-term savings account: they store carbon over millennia, but accumulate slowly. Forests, on the other hand, are like a current account – they accumulate fast, but store carbon in the short-term.

As these ideas about carbon landscapes sunk in, we learnt why drainage ditches had been blocked to raise the water table and plantation conifers were removed in order to restore Kirkconnell Flow, as I have documented in an earlier blog.

As we walked to the heart of the Flow, we sensed through our feet that a peat bog consists almost entirely of water. The topmost living layer of plants is underlain by the plants’ dead ancestors: the moss has captured water to create a lens of peat in what was, ten thousand years ago, a glacial lake. ‘Ombrotrophic’ is a word used to describe raised bogs – this means that nutrients within the peat bog have built up from rainfall only, as carbon was sequestered from the atmosphere via photosynthesis. Poets and scientists in the group were equally fascinated by this entity, and the meanings that can be extracted with a peat core.

Lauren explained how her research techniques allow her to ‘read’ the archive that reaches down through metres of peat – Ann Lingard has already described this very clearly. With Lauren instructing, we learned how to explore the depth of the bog with a ‘Russian’ – an instrument that yields semi-circular depths of peat to researchers and their assistants.

Each time the Russian was drilled under the bog, it came up with about a thousand years of history. The first section, we learned, could be dated by traces of Chernobyl’s nuclear accident and other pollutants of the industrial era. Each sample was placed in guttering, labelled and wrapped in cling film; we bored down, seeing how the dark top layers changed to become lighter and wetter as we got deeper.

After five and a half metres, suspense deepened. Would we reach the boulder clay that was deposited when the last glaciers melted, with our final sample?

Yes! Pale grey boulder clay was drawn up from six metres below.

On 23rd April, the peat core became a conversation piece for a second Borderlands meeting at the Stove. The successive depths of the sample were shown with the Russian corer, alongside drawings I had made in anticipation of peat core analysis. As Lauren pointed out, our imperfect technique meant that this sample cannot be used for scientific purposes – but it offers much for artists to think with.

The science Lauren uses for analysis of a peat core includes proxy measures which age the sample, providing ways to document changing environmental conditions through which the bog has developed.

One of these proxies are testate amoebae – microscopic protozoa with hard shells, in varied shapes. Different species flourish according to how wet or warm the living layer of the moss is.

The books describe them as ‘vase-shaped’, making me speculate about potential Iron Age remains to be found amongst the amoebae.

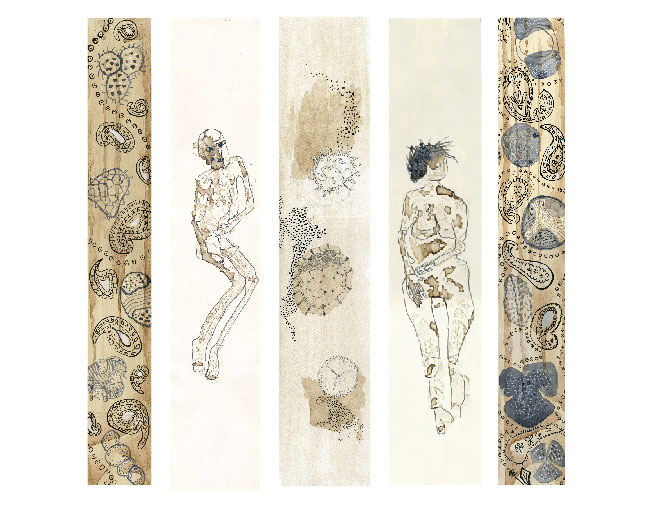

These became intertwined in my studio drawings, as I began to consider the ideas a peatcore may convey.

Pollen grains in the core provide information about which species flourished as the bog grew, making beautiful shapes when seen under a microscope.

I combined the idea of these pollen grains with Russian paisley patterns.

Bog-bodies also came to mind as I prepared drawings in the same dimensions as Russian peat core samples. I would like these to accumulate into a new body of work.

With thanks to Dr Lauren Parry and all who took part in the Borderlands 2 event, held with generous support of the Stove. This event and the ideas it generates will continue to be recorded on this blog.

6 thoughts on “getting down to the Ice Age”