This presentation was given at the invitation of BUND (German Friends of the Earth) in October 2016 to their annual conference in Burg Lenzen, on the River Elbe.

Working the Tweed was a socially engaged arts project in a rural region of Southern Scotland. Artists have led or been involved in similar projects elsewhere – and we hope the ways that artists can work is interesting for you with BUND’s work on the Elbe. This is offered as a pilot project for discussion, not as a finished artwork.

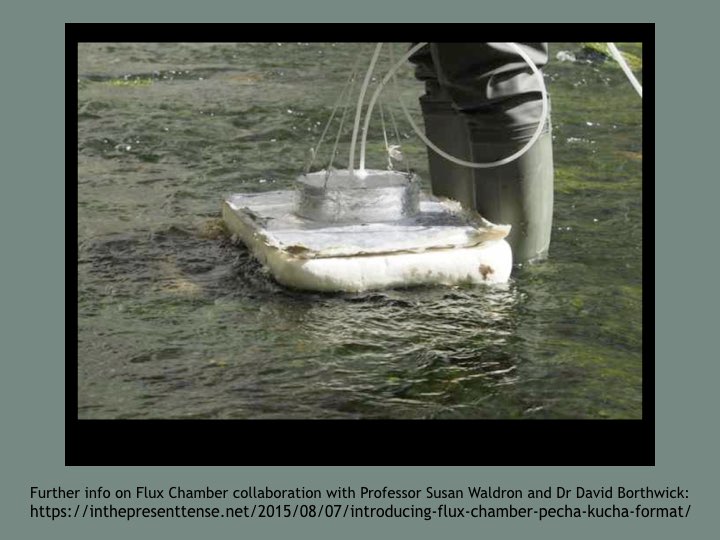

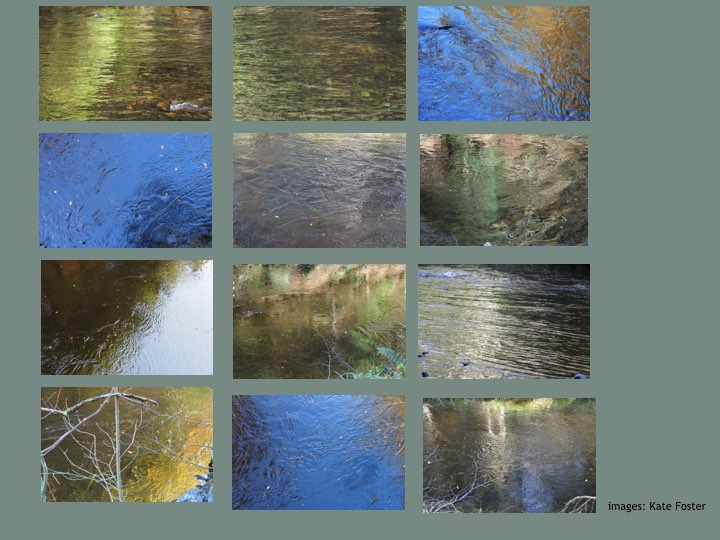

This quote neatly summarises what we hoped to do: to contribute to river culture. Martin Drenthen is a Dutch philosopher who has done considerable work on rivers, communities and place-making. We chose our project title to emphasise the livelihoods offered by the river: how people have managed, used, and shaped it, and how other species depend upon it. We offered our project as a resource for creative practitioners in our region. We also wanted to connect our partner agencies with people who see the river in less instrumental ways.

The project won public funding from the government arts and environmental agencies available via a ‘Themed’ year of Natural Scotland. Additional funding was via LEADER (EU), a charitable trust, and support of regional venues.

It was an artist-led project with partnership working at its core. We approached the two key agencies in our region concerned with sustainable development and environmental protection in the river catchment. Both are ‘bottom-up’ membership organisations.

The Tweed River flows from upland moorlands towards richer agricultural lands, meeting the sea at Berwick upon Tweed. Its last section acts as a border with England. Salmon, trout, and other migratory fish run. Sport fishing is economically important.

The River shares its name with woven cloth historically produced in the area’s small towns. The river was vital to an international trade as it powered the textile mills. The lower reaches were commercially fished. The Tweed has inspired many artists and is now seen as a rural river where nature can be enjoyed. There is a resurgence of interest in renewable hydropower as part of small town regeneration. Several flood protection schemes are being put in place.

This is how Tweed Forum has summarised concerns about the river catchment. Tweed Forum’s Catchment Management Plan helped us structure the project. This adopts the concept of ecosystem services which can be given monetary value. As artists we were also concerned with intangible cultural value.

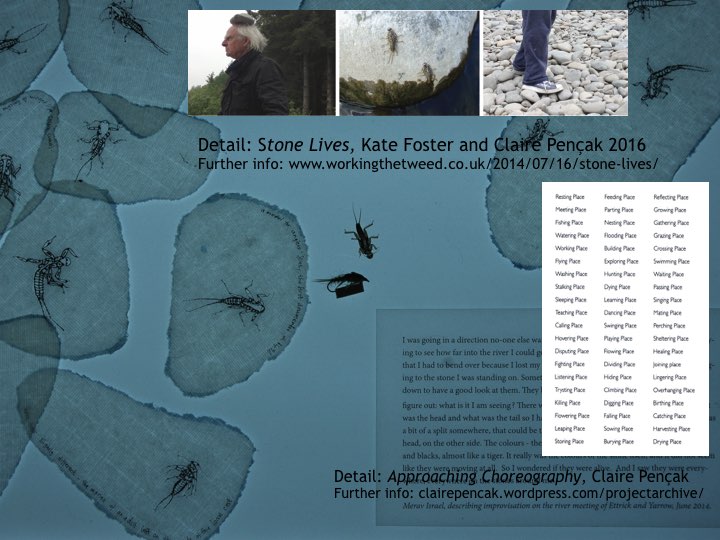

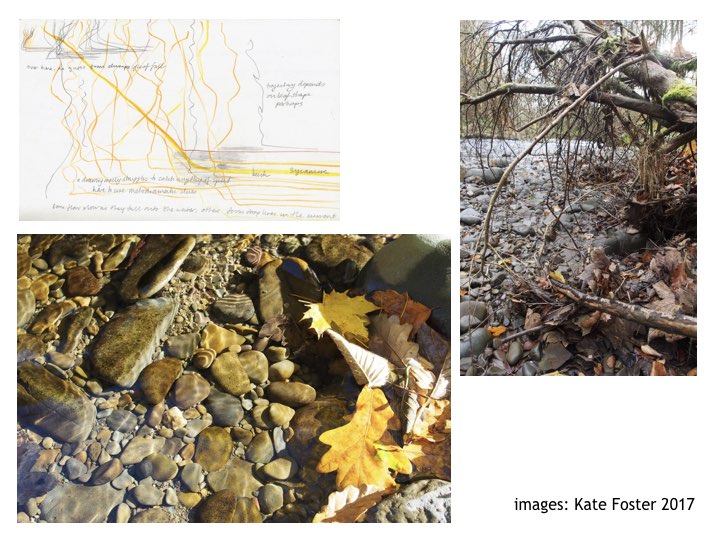

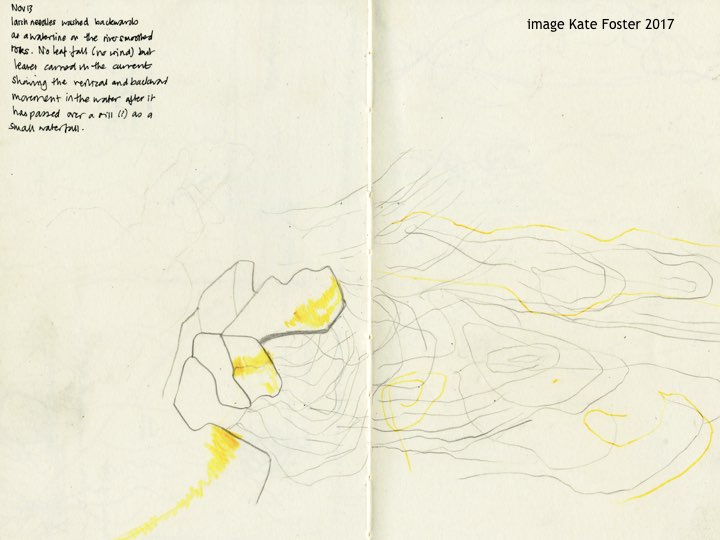

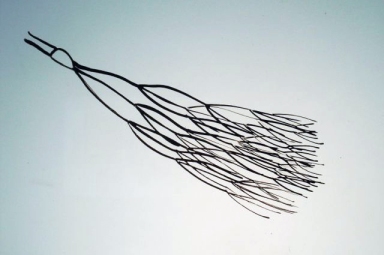

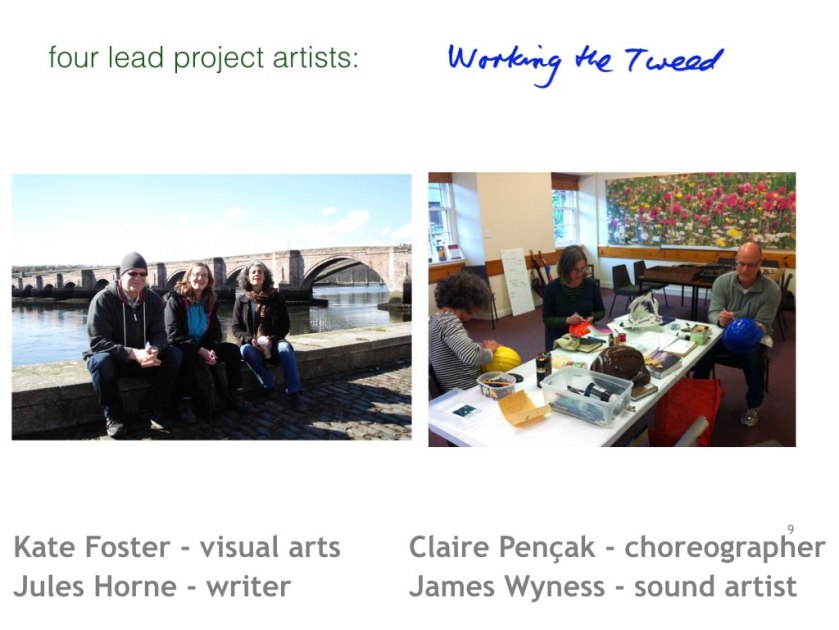

For this project we as artists abandoned the expectation of making individual works. Instead, our role was to use our skills to facilitate conversation, through Claire Pençak’s creative direction. Our different art-forms let us respond flexibly to different contexts.

We had to learn to understand and speak different ‘languages’.

It was a pilot project researching ways to approach future artwork. This project let us develop our own and others’ awareness of the river and build networks across the catchment.

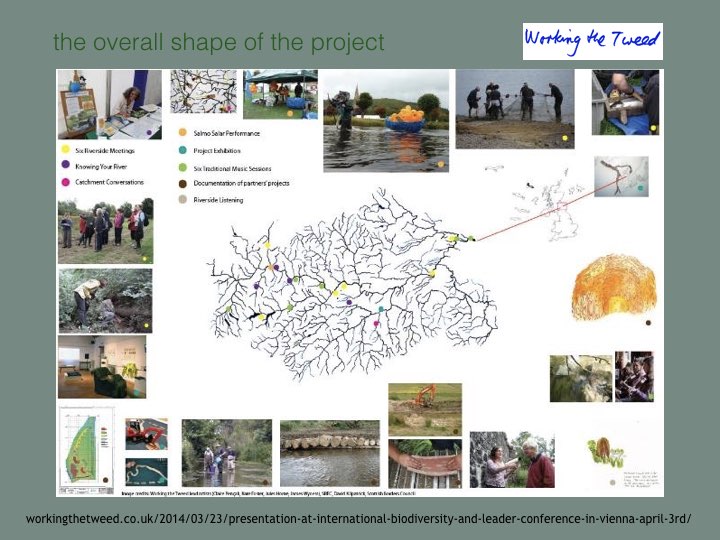

It consisted of many different forms of meeting in unconventional settings, developing the art of conversation around river issues. A copy of the poster is available here.

We will cover three of its eight strands: Knowing your River which toured public agricultural shows; the Riverside Meetings in carefully selected places and open to all interested artists; and Catchment Conversations which brought river specialists together for a concluding event. (The slide mentions the other strands).

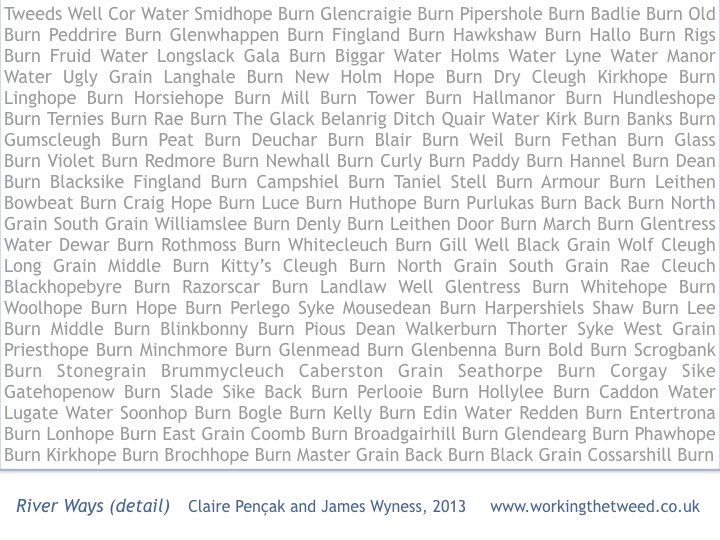

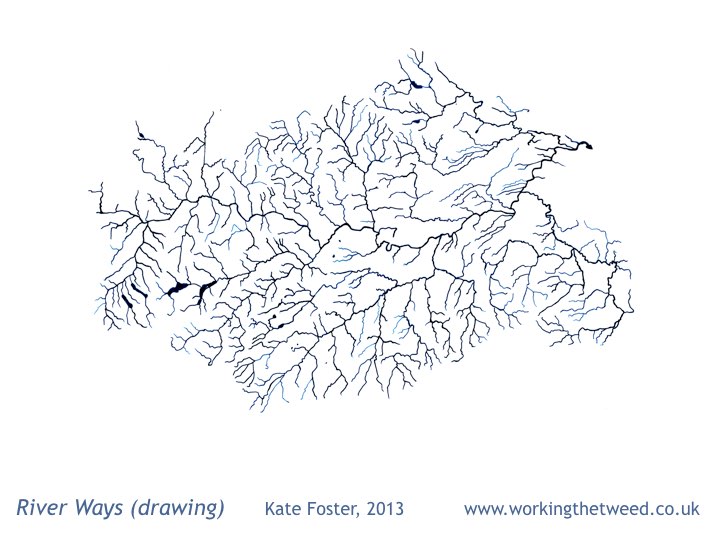

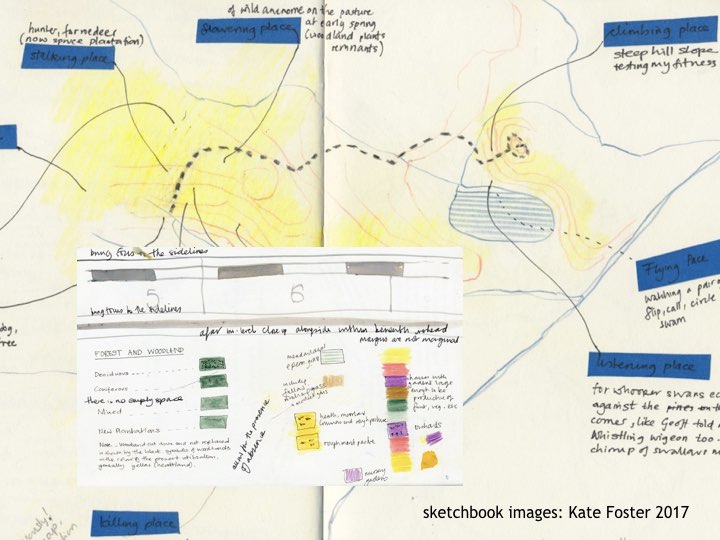

An accurate geographical catchment map is not freely publicly available, but we wanted one for the project. We created a traced drawing offered people a new view of their region. It does not show towns, or river names.

We took this map to agricultural shows – busy summer events in the region. We invited people to locate themselves according to the catchment map. This prompted conversations which revealed a depth of local knowledge and many different ways of knowing the river.

People were interested in this catchment image and it became a motif for the project. The idea of the region as a catchment – rather than a series of small towns with strong civic pride and rivalries – offered a sense of connectivity and cohesion.

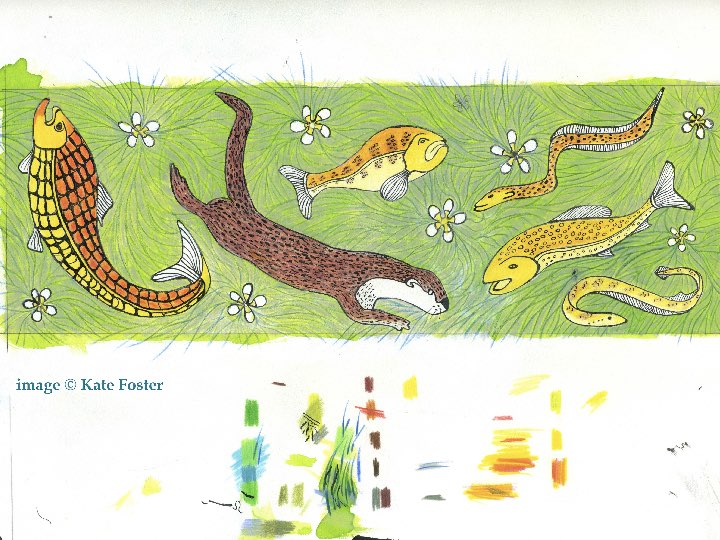

Habitat and Species (from Tweed Forum Catchment Management plan) had a parallel theme of More–than–human (a term from cultural geography). In this photo, an ecologist points out Otter spraints (poo) to a poet. The riverside meetings were informal – no power point! People met at the river and talked freely about their connection to it.

The site for this first meeting was a traditional fishing (Haaf) spot, the fishermen on this occasion were helping a biological survey by Tweed Foundation – an organisation that informs Sports Fishing which now is dominant. Tagging the Salmon gave the meeting a focus. The session ended with a boat trip to the river mouth.

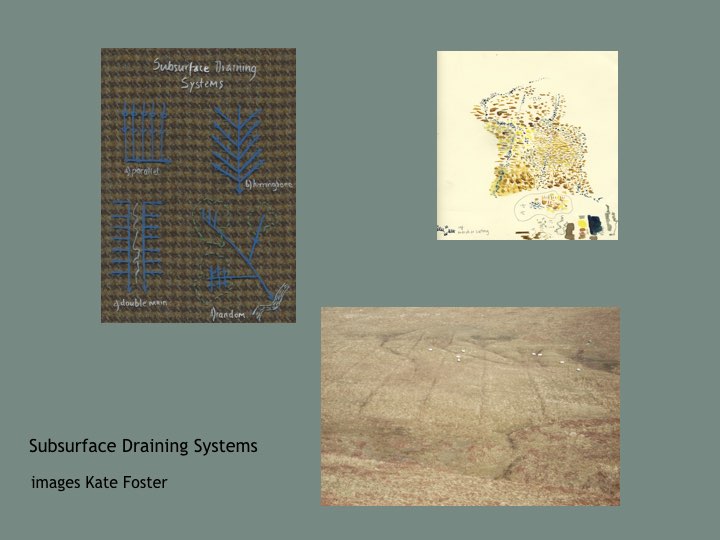

A hydrologist, Professor Chris Spray from Dundee University, described why historical drainage and river straightening had led to this stretch of river being graded poor by EU Water Directive Framework. We looked at the groundworks involved in re-meandering the river (which are now considered successful and are being extended).

A local school teacher attended and later took a class to this site for a creative writing project on re-meandering.

This was at Abbotsford House, culturally significant because it was the writer Walter Scott’s residence (an important figure in Scottish history).

Caulds were barriers originally created for industrial water power. This innovative renewable energy scheme was popular locally, and interesting to watch too. A fish pass was tailor-made for migrating fish, lamprey and eels (though people were not sure if this really worked) as well as salmon.

Megget Water is Reservoir in the uplands, built in the 1950s to supply water to Edinburgh. This is a protected site because of water security issues, and it was exciting to get access to this dam through our growing project network. Local people and environmental managers came along, who would not normally be permitted to go there.

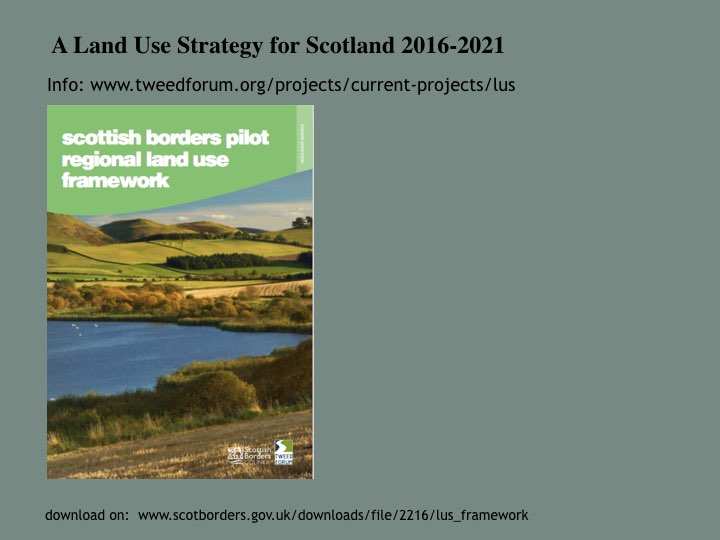

We discussed the Government’s pilot Land Use Strategy (Climate Change Scotland Act) alongside the recent Scottish Borders Region Cultural Strategy. This drew out the topic of cultural landscapes, and the interconnection with culture and land use. We reflected on how short-term political cycles do not achieve sustainable management , and how local actions have impact elsewhere.

There is an account of our artwork in parallel to the Land Use strategy here.

This was the culmination of the project, directing attention to the future and action. We offered this event to our partner agencies as a variant of public consultation.

This brought together ten people by invitation, with varied relationships to the river e.g. a scout leader keen to get young people canoeing, a development manager for community energy projects, and a forestry manager, a curator, and a digger driver. Many had been to a previous event.

The venue was an inspiring furniture maker’s riverside studio – we decided not to use a standard conference centre. An arts setting can stimulate different ways of thinking.

The outcome was a brainstorm on what action to take on three key themes that had emerged through the morning session. Documentation is available as a pdf via http://www.workingthetweed.co.uk .

How did we structure this event? The morning session used objects people had brought to introduce ourselves in relation to the river. For example, a digger driver brought a collection of historical clay drains, one of which had a small hand print on it from the person who made it.

Participants also each brought two photographs, illustrating firstly something working well on the rivers and secondly something they thought needed improving.

These are the themes for the afternoon workshop groups, themes that had emerged in the morning. We directed conversation to possible action. This was a very different experience to going to a conventional meeting focussing on a specific problem (eg flood protection), like formal public consultation would do.

These two slides recap the strategies that we brought as artists to the design of the project. We needed to think laterally, develop symbolic language, make connections, network, use interdisciplinarity (requiring many meetings between lead artists).

There are potential conflicts between generating participation in cultural activities and being an environmentally responsible organisation.

We aimed to conduct the project sustainably – eg use of materials, or providing shared minibus transport to riverside meetings to minimise use of private car.

Our intention was to take complex issues ‘off the page’ and into people’s imagination.

These are the material ways we communicated about the project to different audiences – from face to face, exhibition, to digital media. We made a DVD as a project summary, with reflection about collaborative practice and how arts practitioners can contribute to shaping the future of the catchment.

The digital element has given the project an afterlife, as a library for reference and an international platform. For example a sound map was developed through Aporee as a digital means to post interviews, music, and sounds of places where they were recorded.

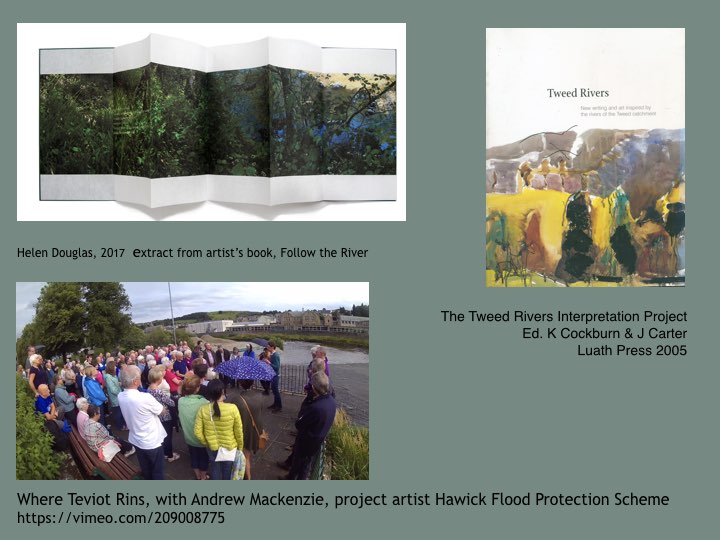

Working the Tweed went some way to persuade funders, land use mangers and artists what creative practices can contribute to thinking around land use and environmental issues. It helped us appreciate that River Culture already strongly exists in our region, and think of further ways to get involved and help develop river connected projects.

!

This project introduced a practice of including artists as part of teams working towards rural development projects, for example as a project artist for the Hawick flood protection schemes. Andrew Mackenzie became involved in public engagement and contributing to scheme design.

Thank you!