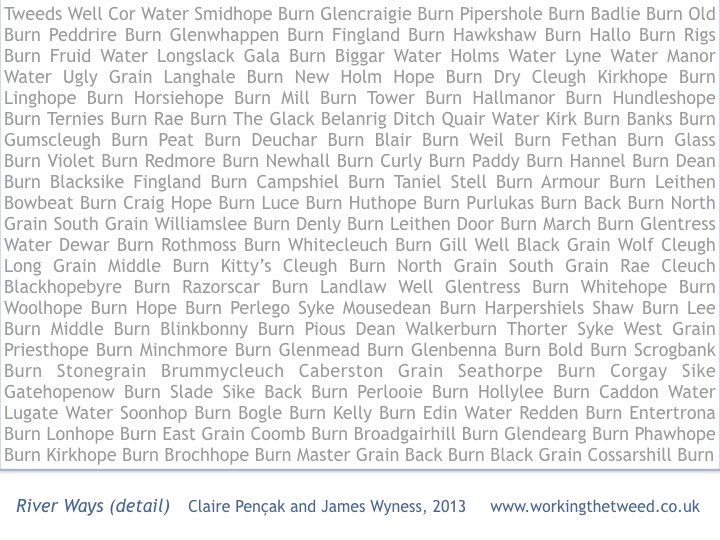

A drawing, a map and a guide are connected by the flow of water in the Tweed tributaries.

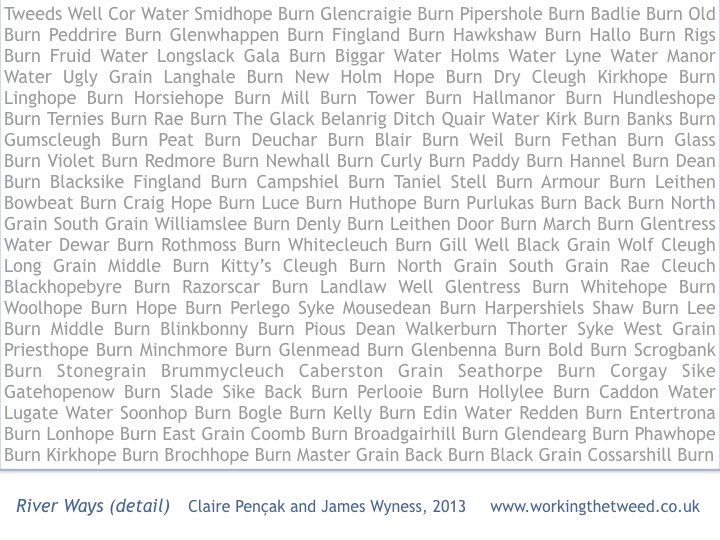

This is soon to be published as a pecha kucha talk . It is about a catchment drawing, a Land Use map, and a guide to how carbon moves for water to air. The connecting theme is the flow of water in the Tweed tributaries. To begin, here are some of their names, collated for a project I was part of, “Working the Tweed” (2013)

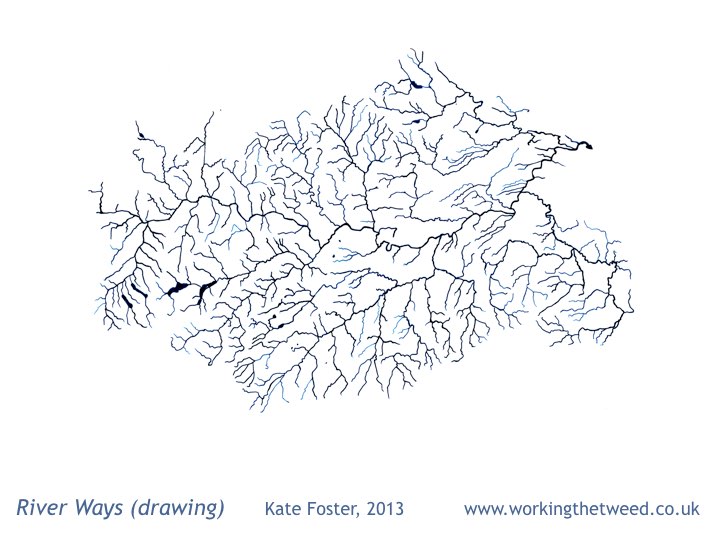

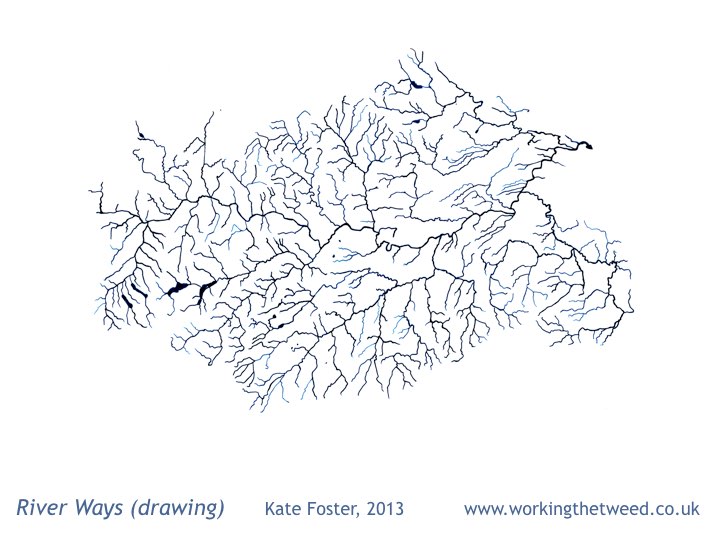

Catchment maps are handy things for a project to have, but we needed one that was affordable. So I traced these River Ways to make a talking point on our project stall at agricultural shows. The drawing became a project motif. The Tweed is a very dendritic river – this drawing leaves out fine detail.

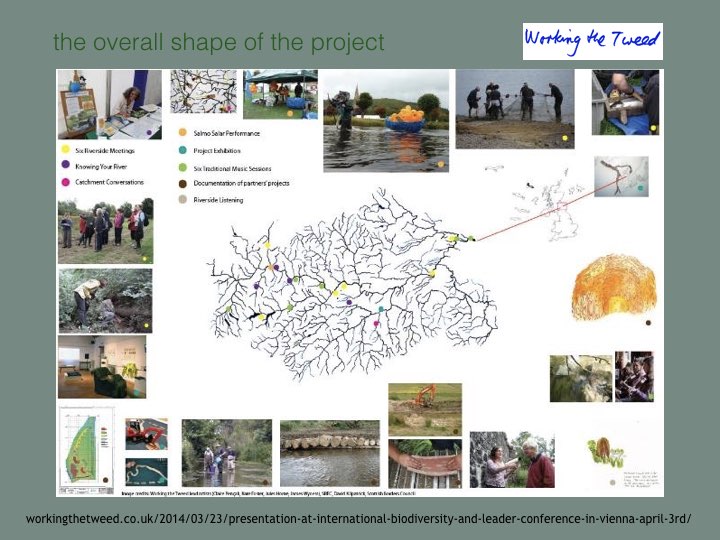

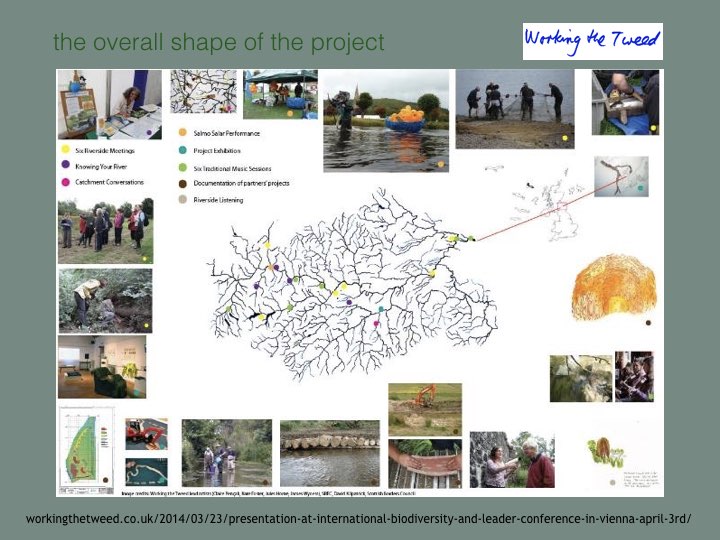

This slide gives an impression of the project Working the Tweed. The Borders region is defined and connected by rivers, though people often think of it in terms of its towns. We learned that many people know their River Ways really well (and could point out inaccuracies).

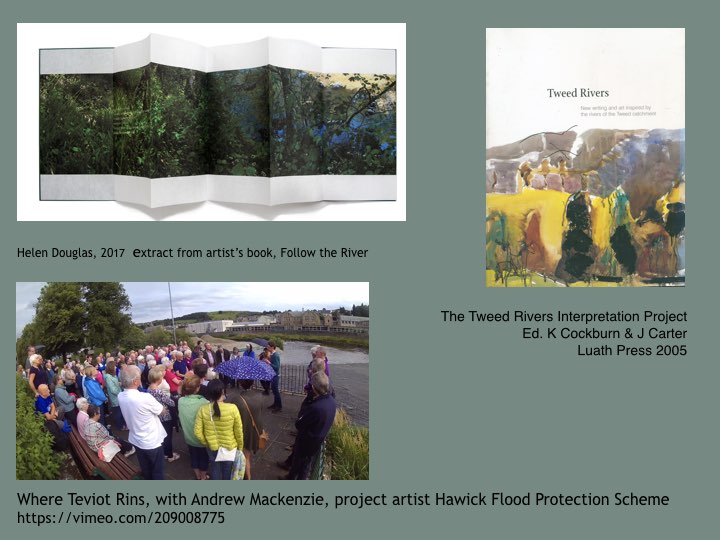

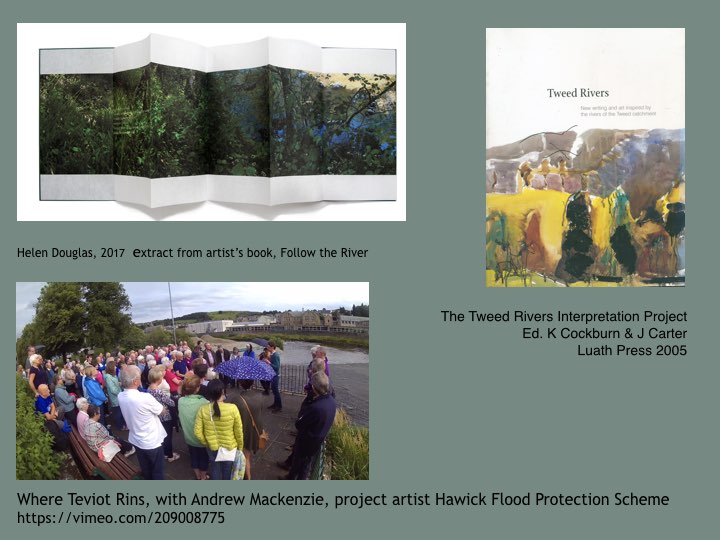

Of course, many other artists have been inspired by The Tweed – these are just three that I have followed. Helen Douglas’ sumptuous bookwork Follow the River developed in the Yarrow Valley ; the Tweed Rivers Interpretation Project; and Andrew Mackenzie as project artist with the Hawick Flood Protection scheme.

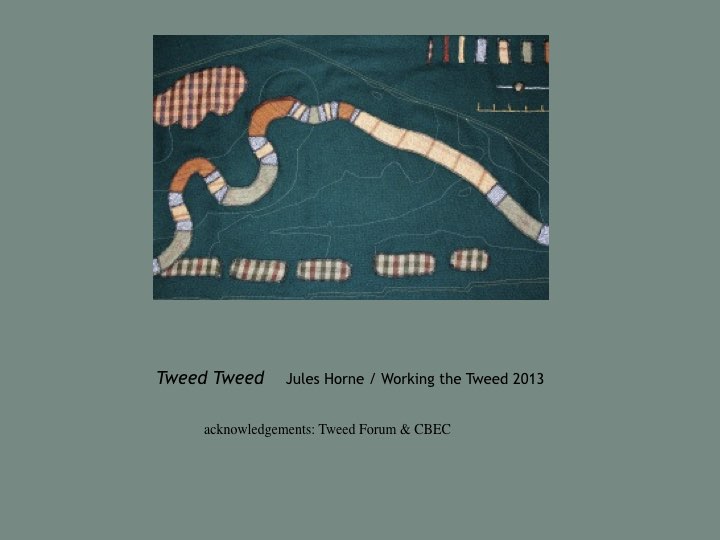

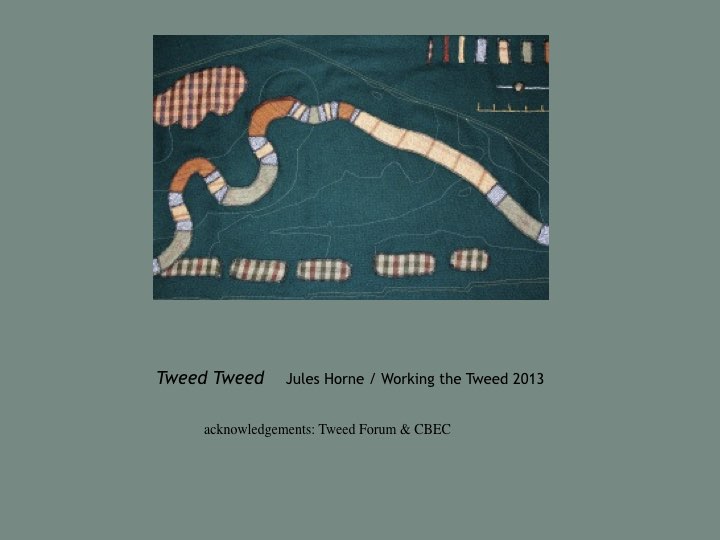

Here is Jules’ Horne’s Tweed Tweed made in cloth. It adapts an engineers plan for a re-meandering project at Eddlestone Water (near Peebles). These works were led by Tweed Forum. We showed this work with a toy-digger so people of all ages could help make the river meander again.

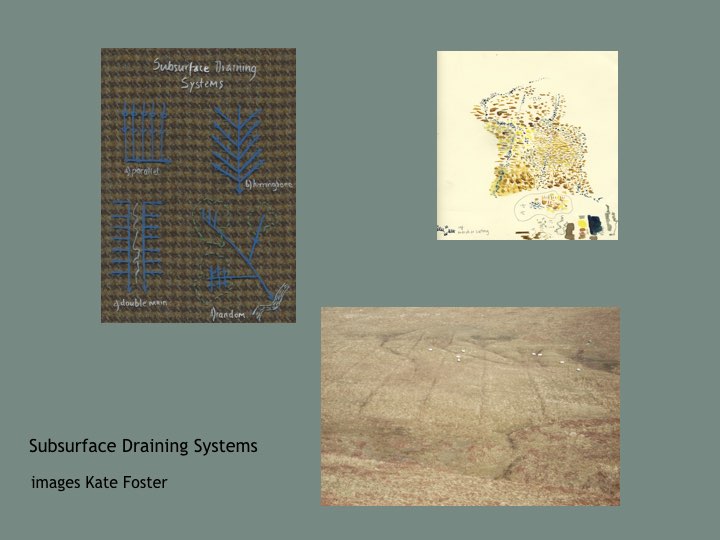

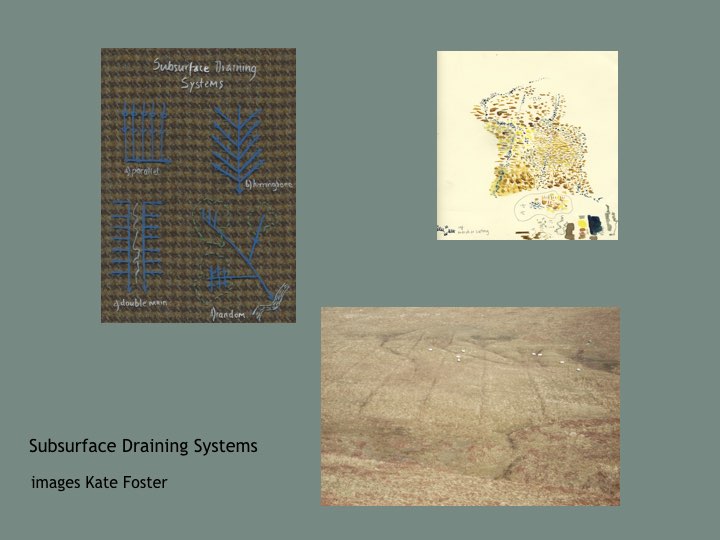

At some point, I realised I should think about Drains too. People have been building a second kind of catchment over the centuries, rushing water to the sea. I began to look for drains in the landscape, and get interested in Subsurface drainage patterns.

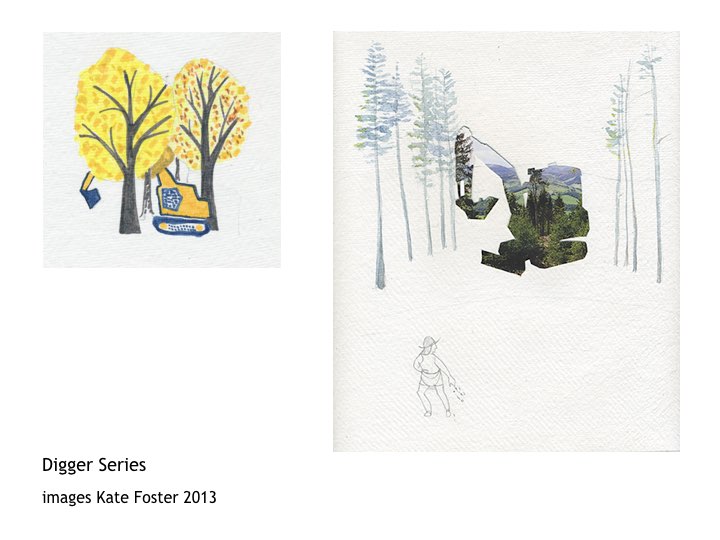

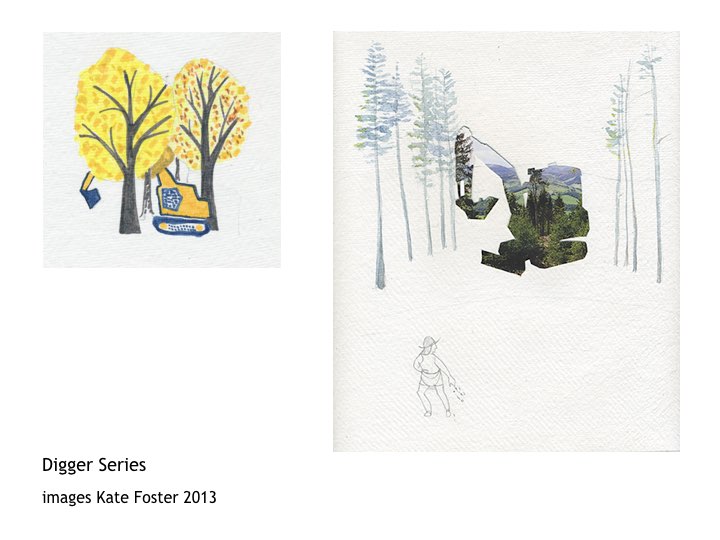

I also have become slightly obsessed by diggers (perhaps I’m not the only one). You see them everywhere when you start looking – performing Landscape Service and doing plenty of Groundwork. But they do seem to hide when it comes to Landscape painting and photography.

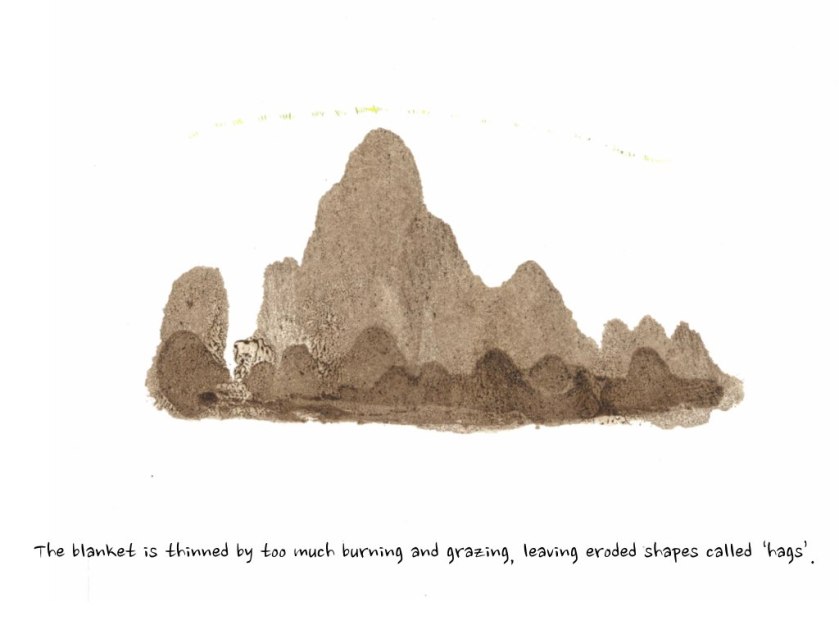

Through the Tweed project, I and the other lead artists became involved in Pilot Land Use Strategy in the Borders, led by Tweed Forum as part of Scottish Climate Change Legislation. The consultation process focussed on maps and was framed by the concept of ecosystem services. The technical language of ecosystem services can be daunting …

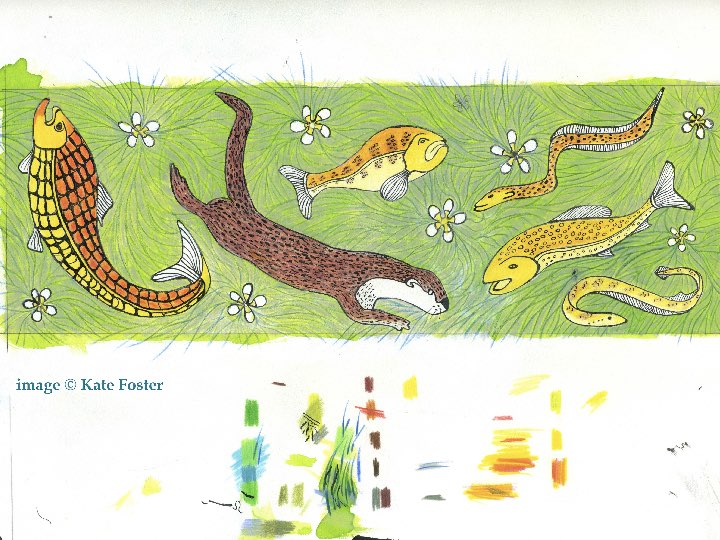

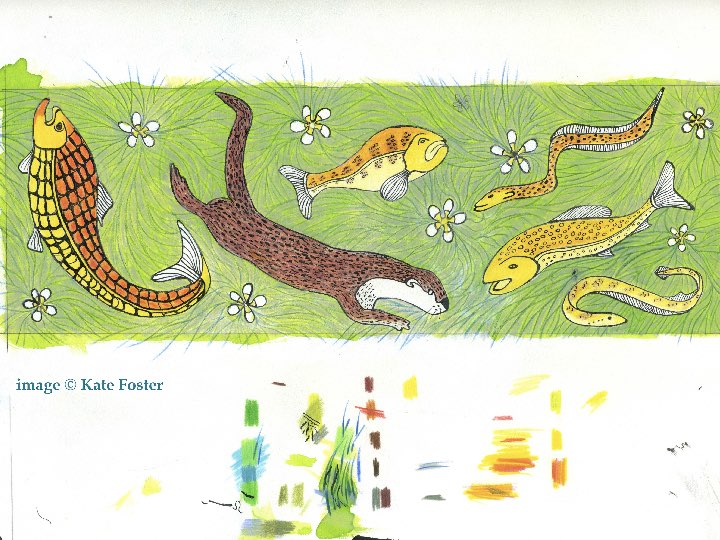

… but every person and every creature is affected by how humans use land. There’s various ways artists’ can contribute ‘intangible values’ and ‘cultural meanings’. As a starter, here’s the Tweed’s ‘indicator species’ – including salmon who need to migrate to cold Arctic waters.

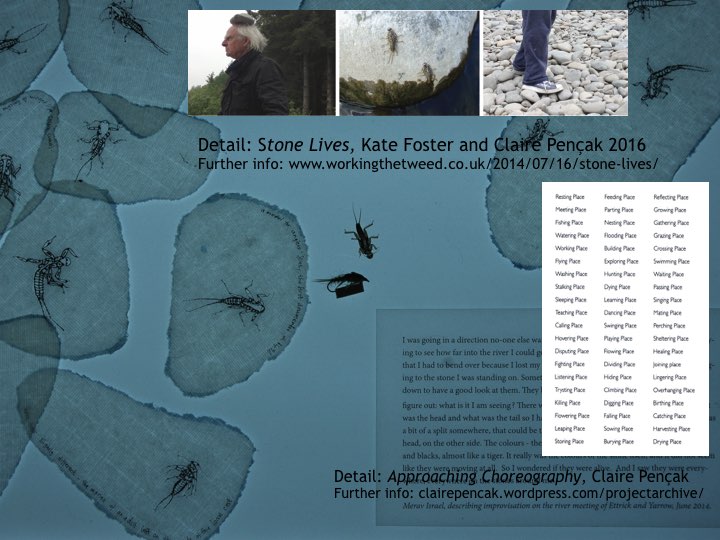

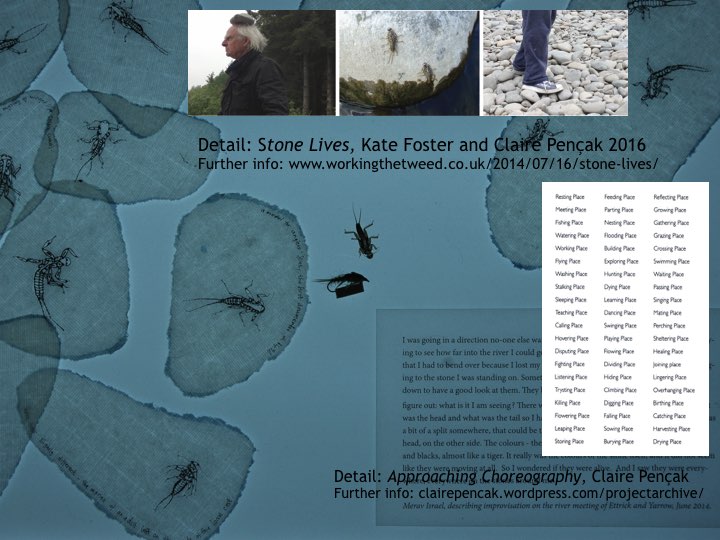

Stone Flies are a favourite food for salmon. Improvisational dancers also paid attention to their midsummer emergence on the riverbank. Stone Lives – led by Claire Pençak – developed as a result. This includes a dance score about personal associations with what happens in particular places.

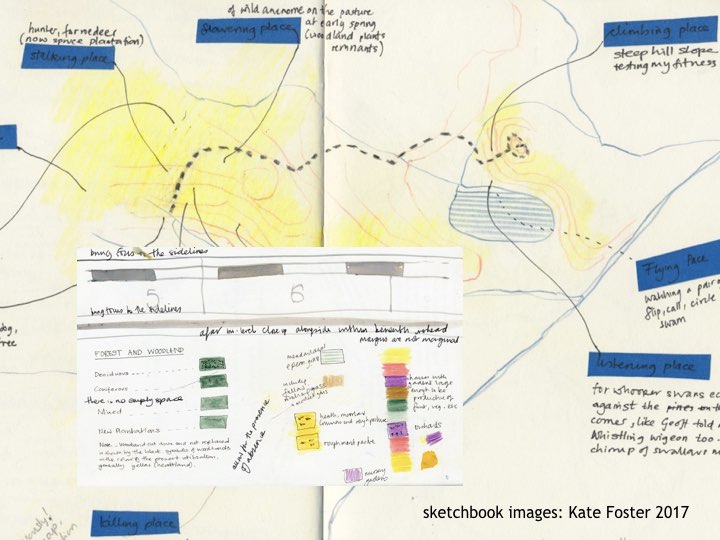

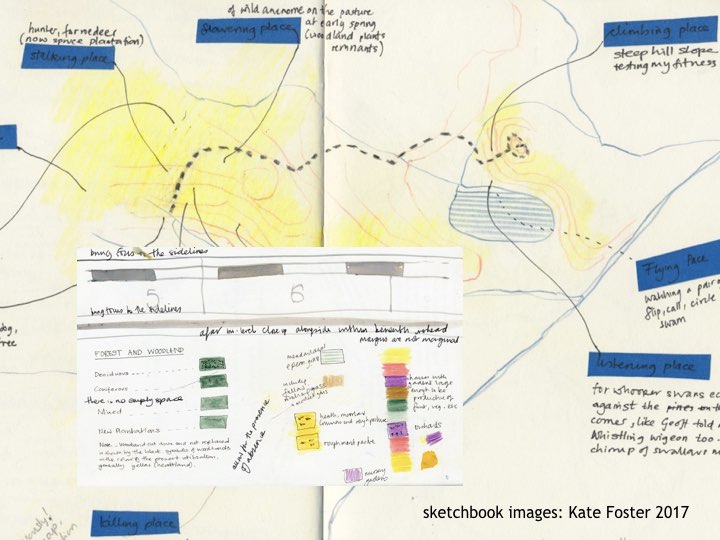

The 1930s Land Utilisation map is in the Mapping the Borders exhibition – it is still in copyright. Here’s a hint of what it looks like. This sketch was an experiment in using Claire’s score. The Land Use map itself is very colourful indeed, with yellow uplands of moorland and heath and flowing towards brown and green valleys, and red or purple towns.

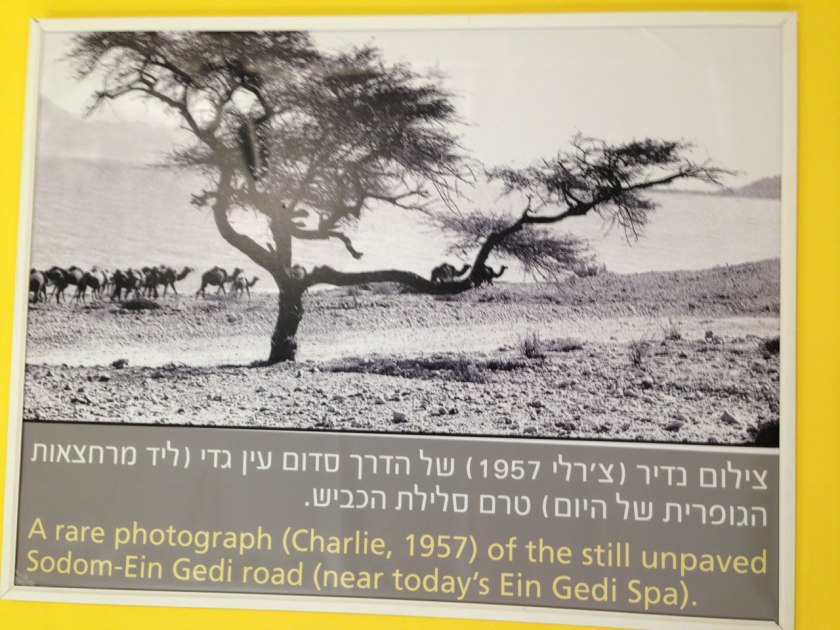

The 1930s map gives bright colours to times I have otherwise glimpsed through black and white photos. I imagine walking in these uplands then – curlew cries, shepherd’s calls, dark skies with crisp cold autumns … but perhaps the colours add gloss to what were hard ways of living.

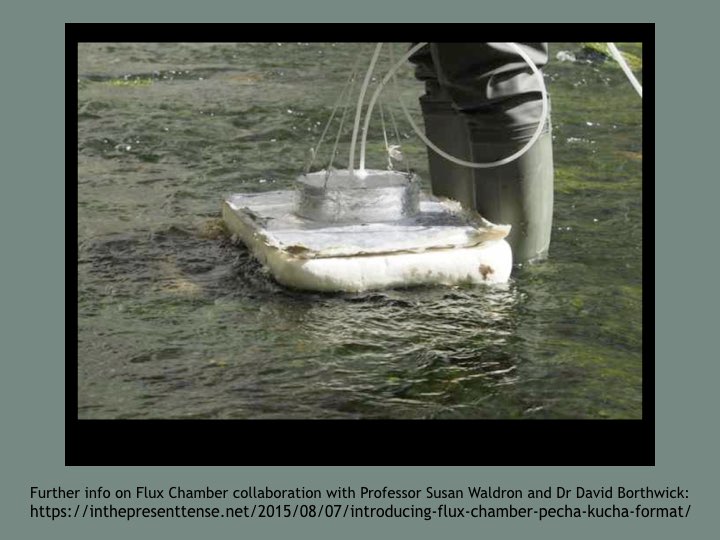

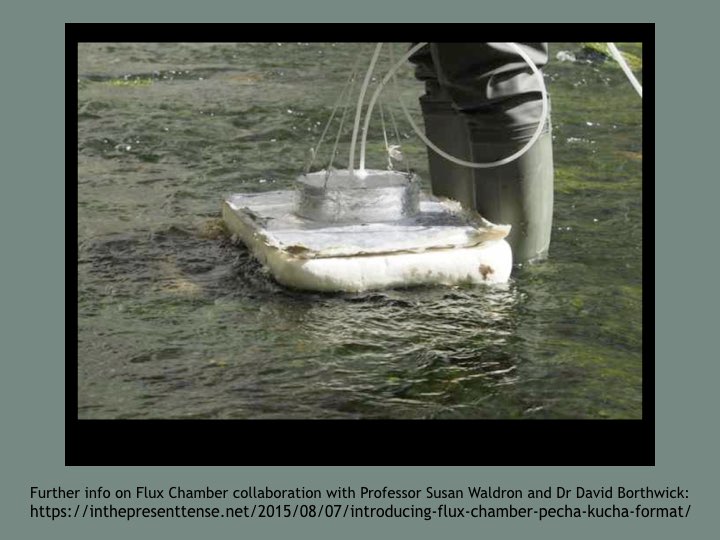

So, next, this is a scientific instrument – a Flux Chamber that measures how much carbon dioxide is released into the air from a flowing river. The amount of carbon being released as gas depends on the time of day, what season it is, and how the land is being used. Flux Chamber became the title for an interdisciplinary project about carbon landscapes.

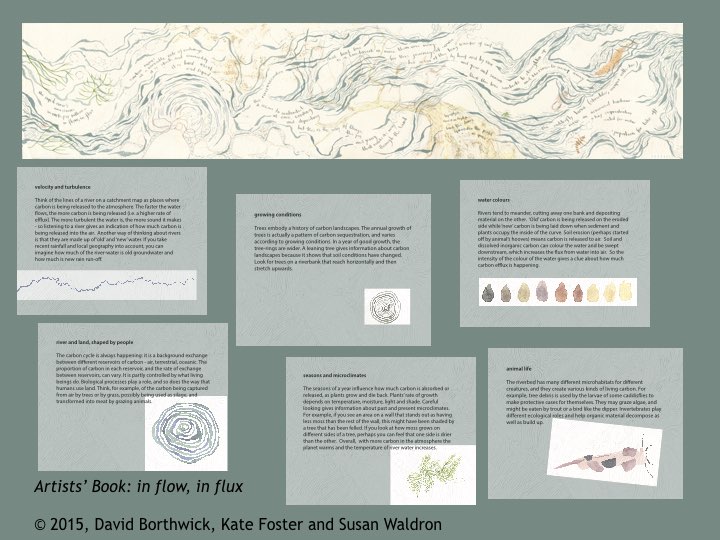

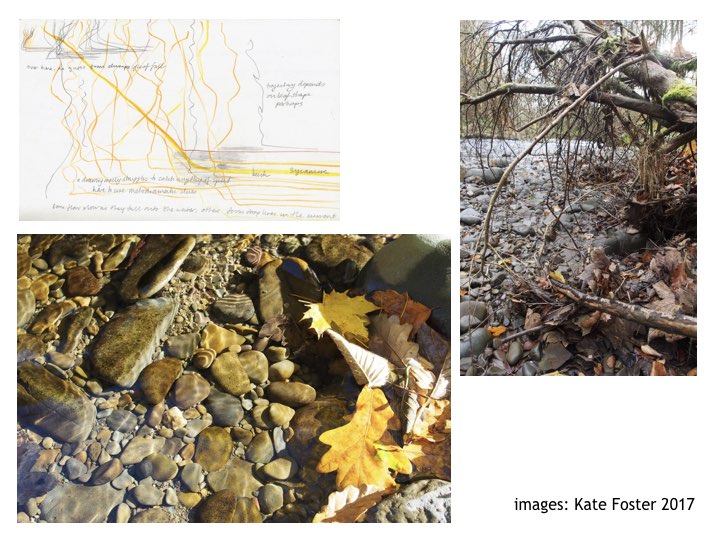

You cannot sense directly when carbon is moving fast from water to air, but you can learn to read signs of when it is likely – when the river is turbulent, brown and noisy. I piloted a ‘guide’ to carbon landscapes with a biogeochemist and a scholar of environmental literature.

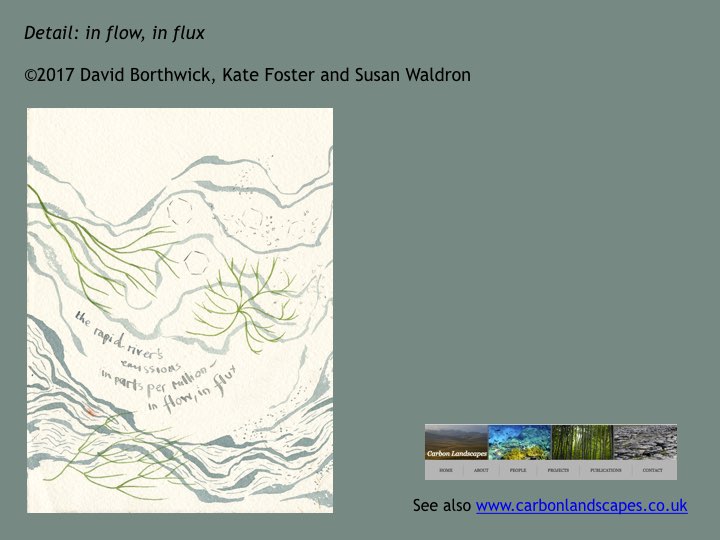

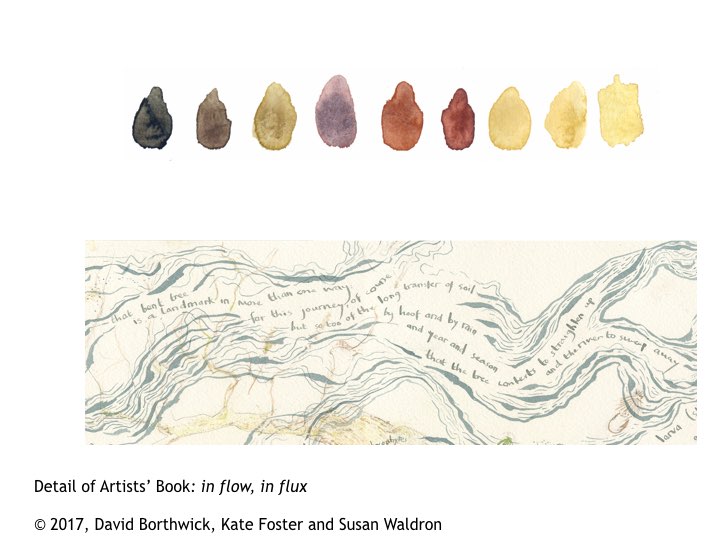

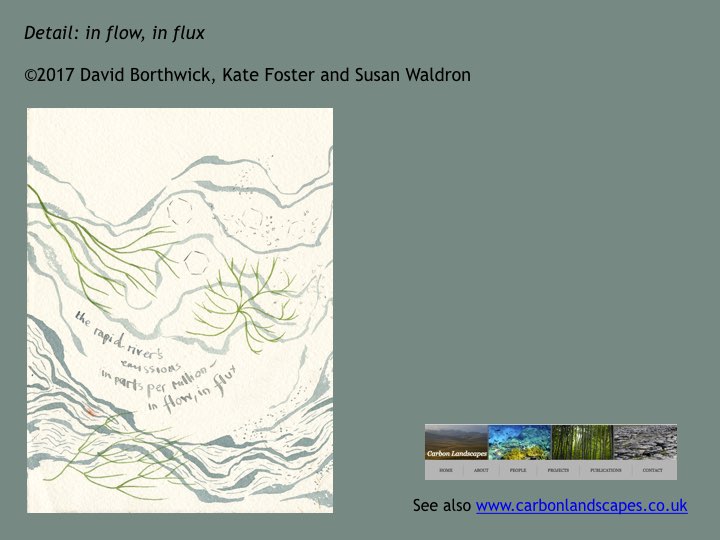

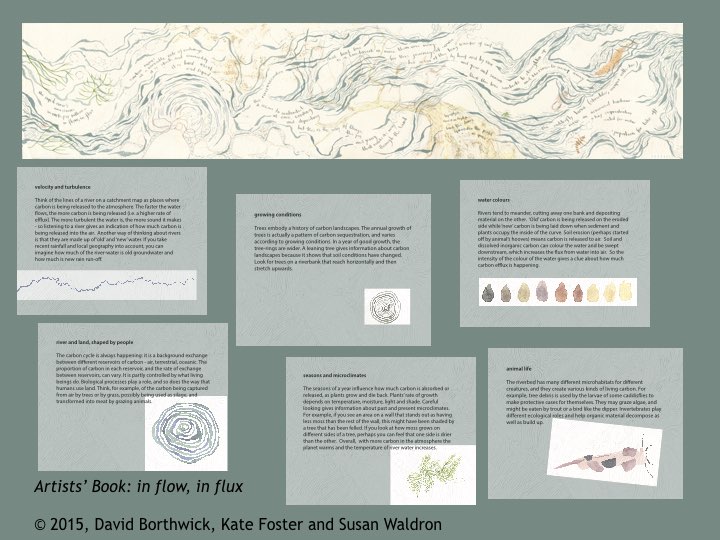

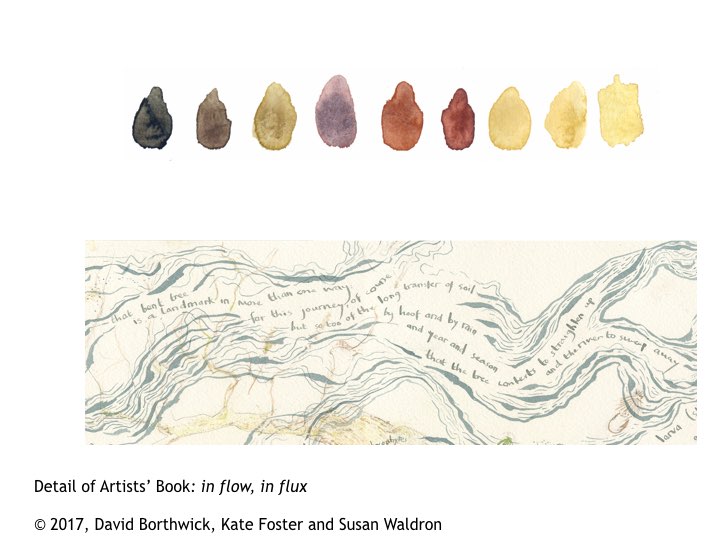

You can see this guide at the exhibition. It opens with an invitation: think of the lines on a catchment map as places where carbon is being released into the atmosphere. This piece combines Susan Waldron’s scientific observations with poetic responses by David Borthwick, and my drawings.

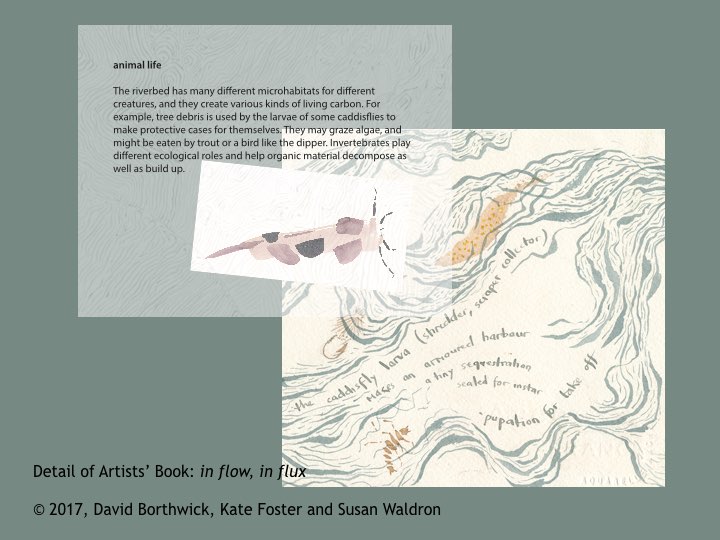

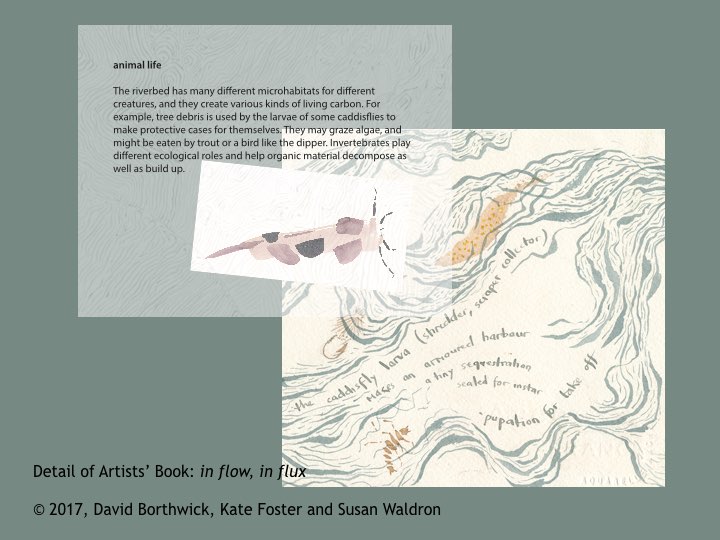

Animal life plays a role too. Caddis flies – like Stone Flies, need clean waters and live in fast flowing upland streams. Expressed as poetry by David Borthwick:

.. the caddisfly larva (shredder, scraper, collector)

makes an armoured harbour

a tiny sequestration

sealed for instar

pupation for take off …

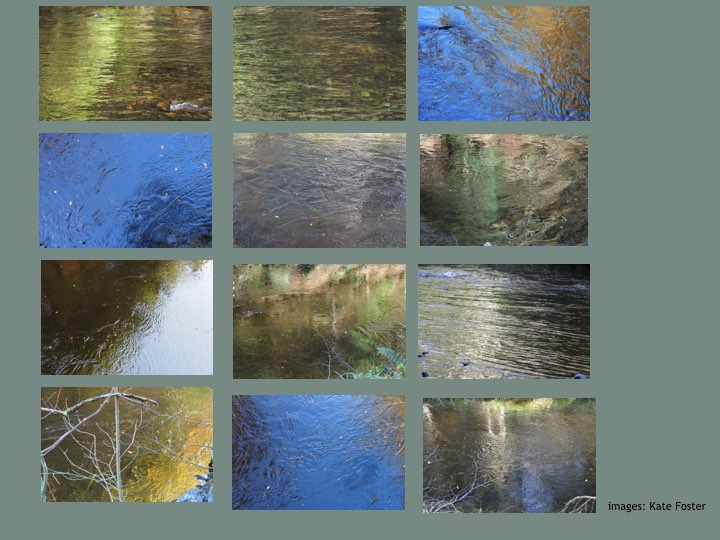

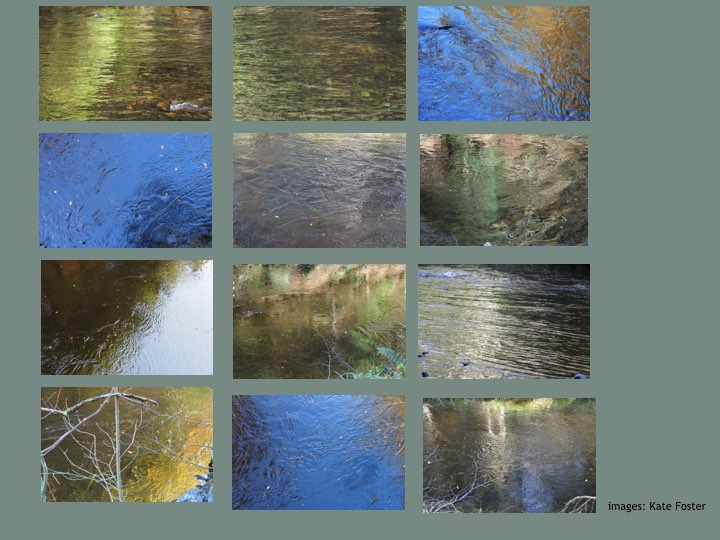

Another of the six pages is about Water Colours:

‘ soil and inorganic carbon colours the water and is swept downstream, which increases the flux from water into air. So the intensity of the colour of the water gives a clue about how much carbon efflux is happening.’ (Susan Waldron)

These are colours of clear water of the upland River Yarrow, drawn out by the sun. The range of colours appeal to the senses, more alluring perhaps than after heavy rainfall when the river becomes dark brown.

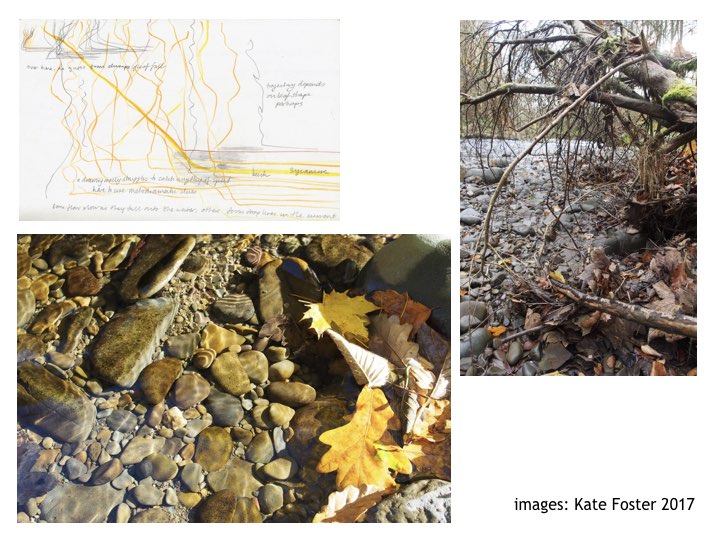

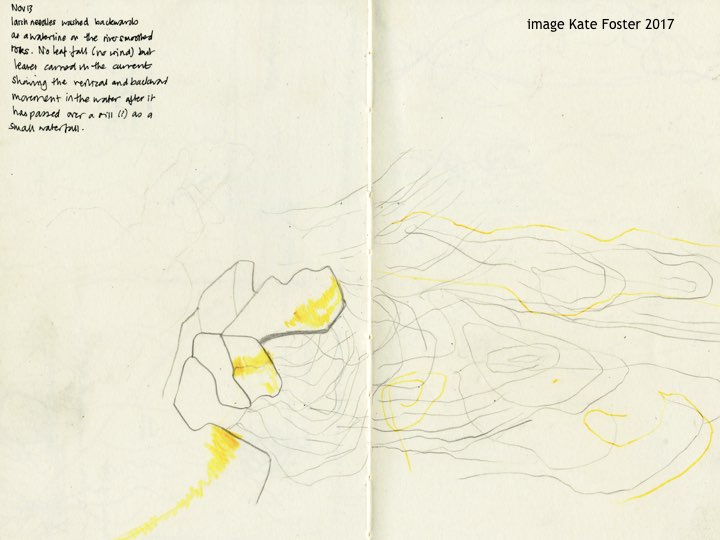

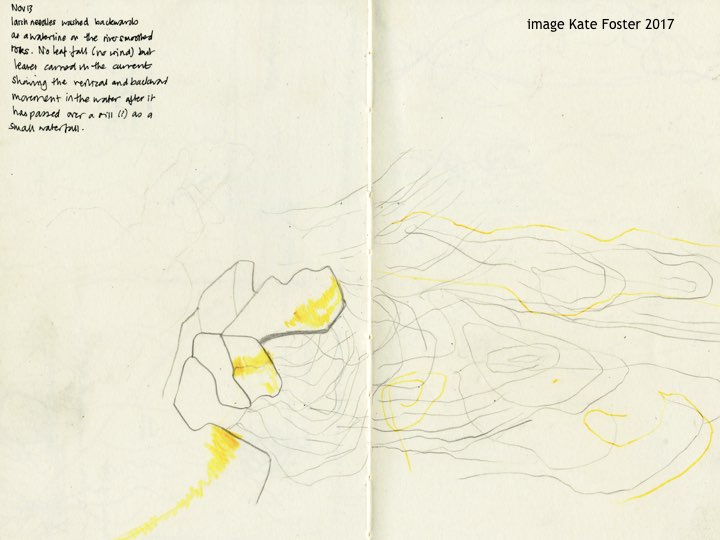

You can’t feel a river shedding carbon directly, but we can watch the leaf-fall onto its surface. We can see leaves snagged on trees at the river bank, left by previous torrents. Through drawing, I find meanings of a specific place which are not expressed by technical reports. For example, this next drawing about how autumnal leaves move in a swirling current.

With winter rains, the rivers will become torrential, opaque brown with silt. I find this sight compelling and formidable.

The fears, hopes and meanings I find in places keep shifting around the metrics of mapping and surveys.