I found myself creating microtopographies and envisioning a restored Raised Bog.

I began by wanting to characterise ‘Bare Peat.’ For people involved in peatland restoration, Bare Peat is an alarm signal. It is an eroded face of the landscape where carbon changes its form and moves into the atmosphere.

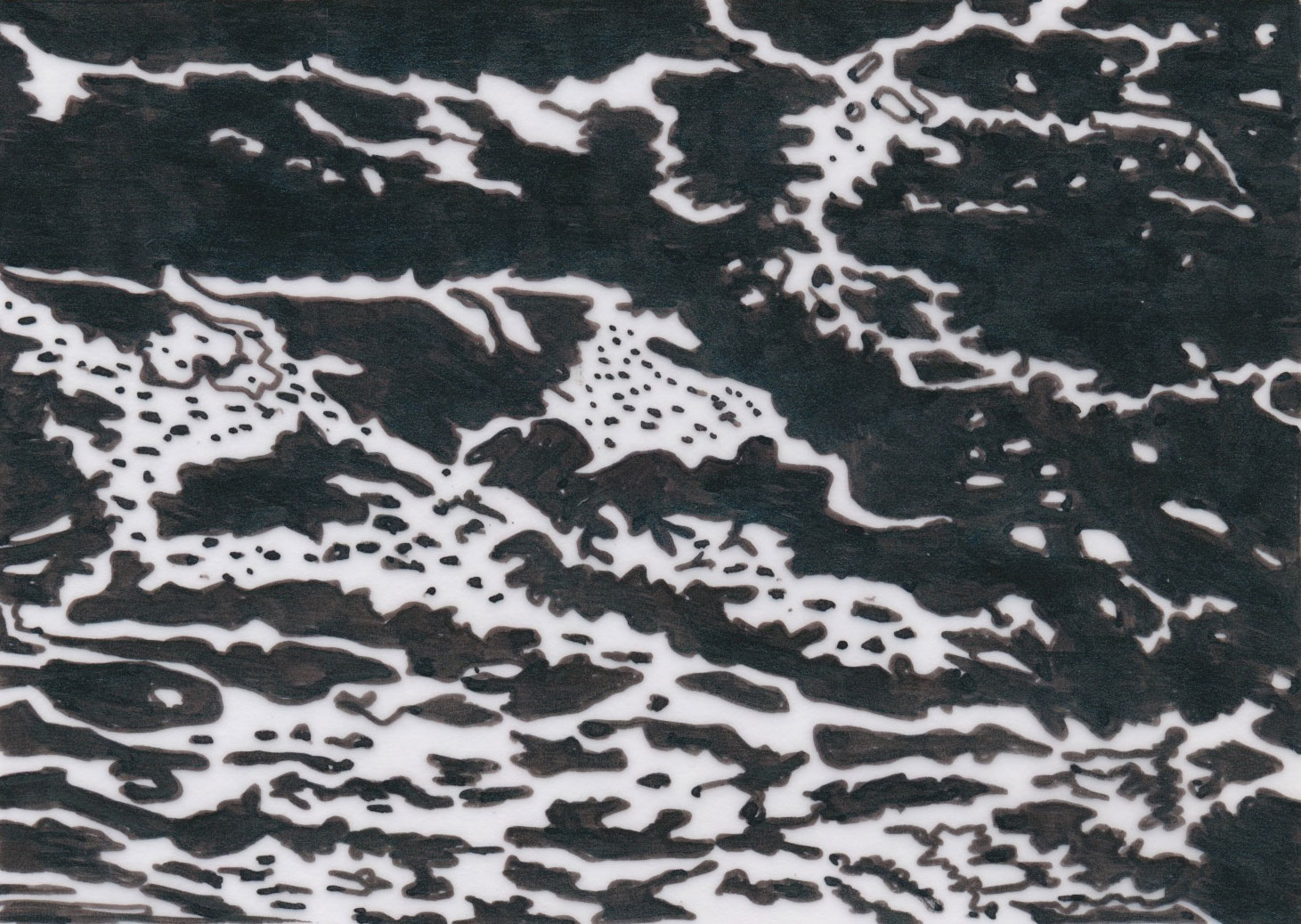

Peat erosion can be considered scientifically at a microtopographic scale. I referred to an authoritative text (Evans and Warburton, 2007:181, Figure 7.6) and focussed on nine photographs of different textures of bare peat denoting different erosion patterns, resulting from wind or rain.

Microtopographies? This is a word conveying detailed geographical study of small surface areas. This study helped me recognise the details of the processes by which peat is eroded. The description given with Warburton’s photographs gave a feel of the processes, such as ‘smooth surface of redeposited peat’ or ‘major step or wash front advancing from left to right.’

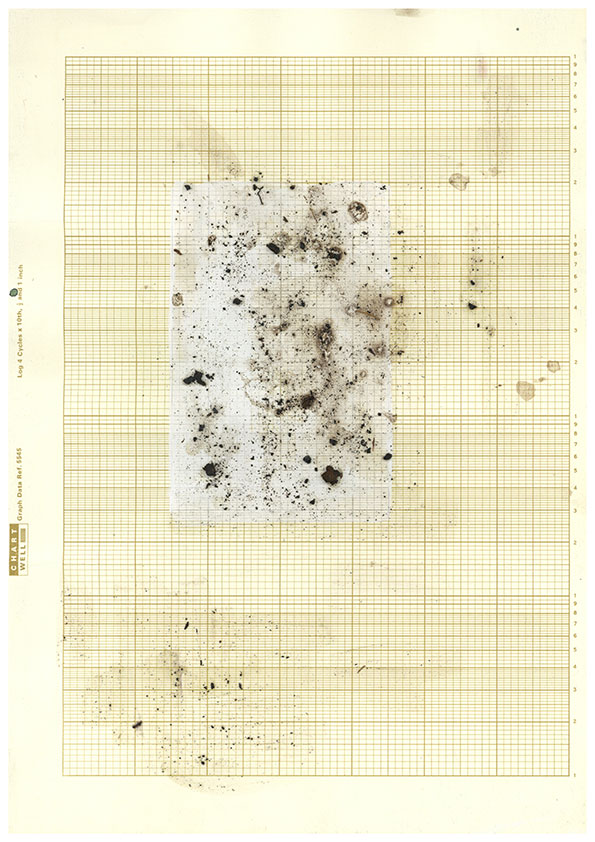

I explored ways to represent the textures of bare peat – through drawing, frottage, and printing, on different papers.

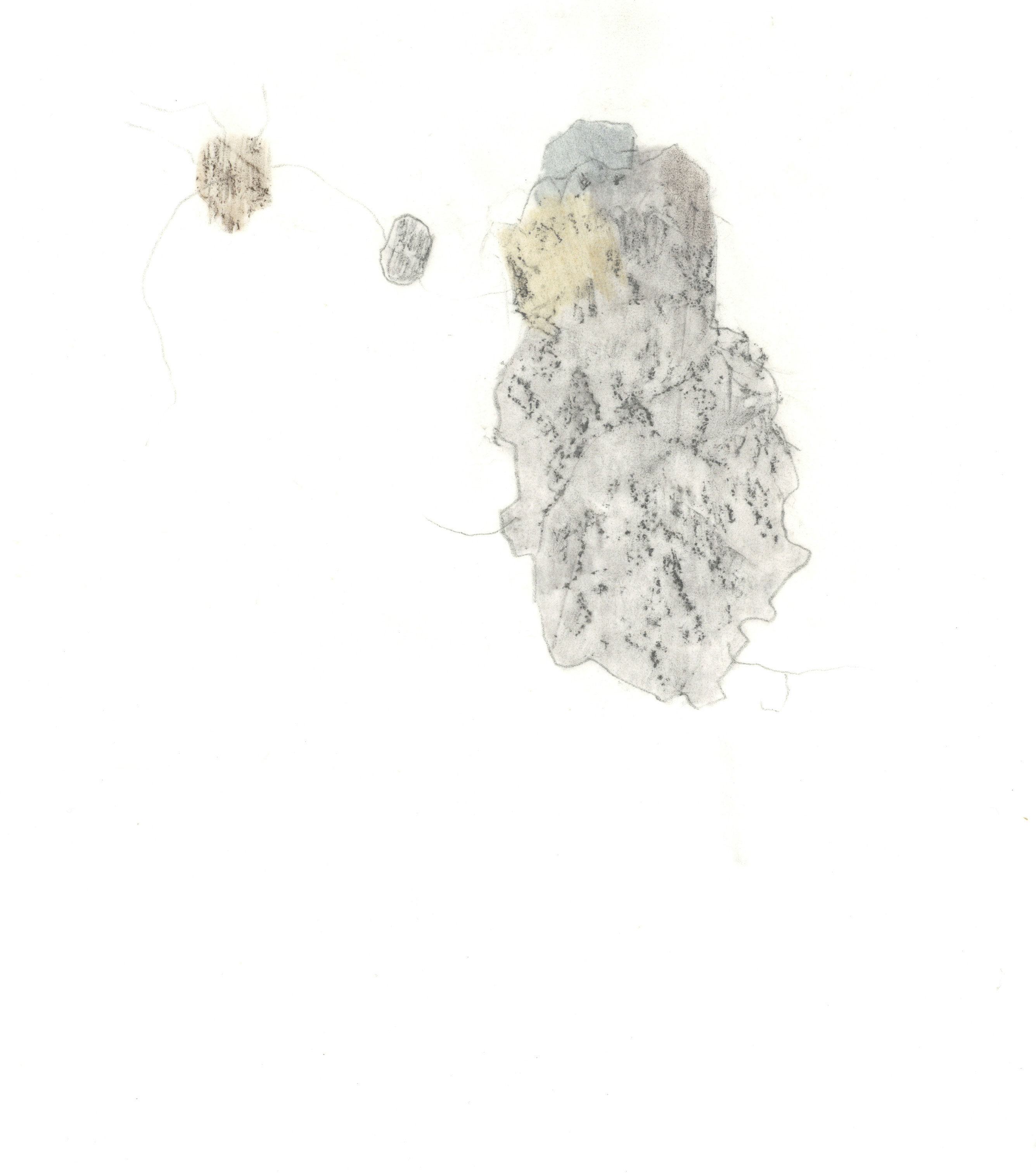

Drawing a cut peat from Lewis, I observed the presence of grassy fibres binding small segments of compressed peat moss together.

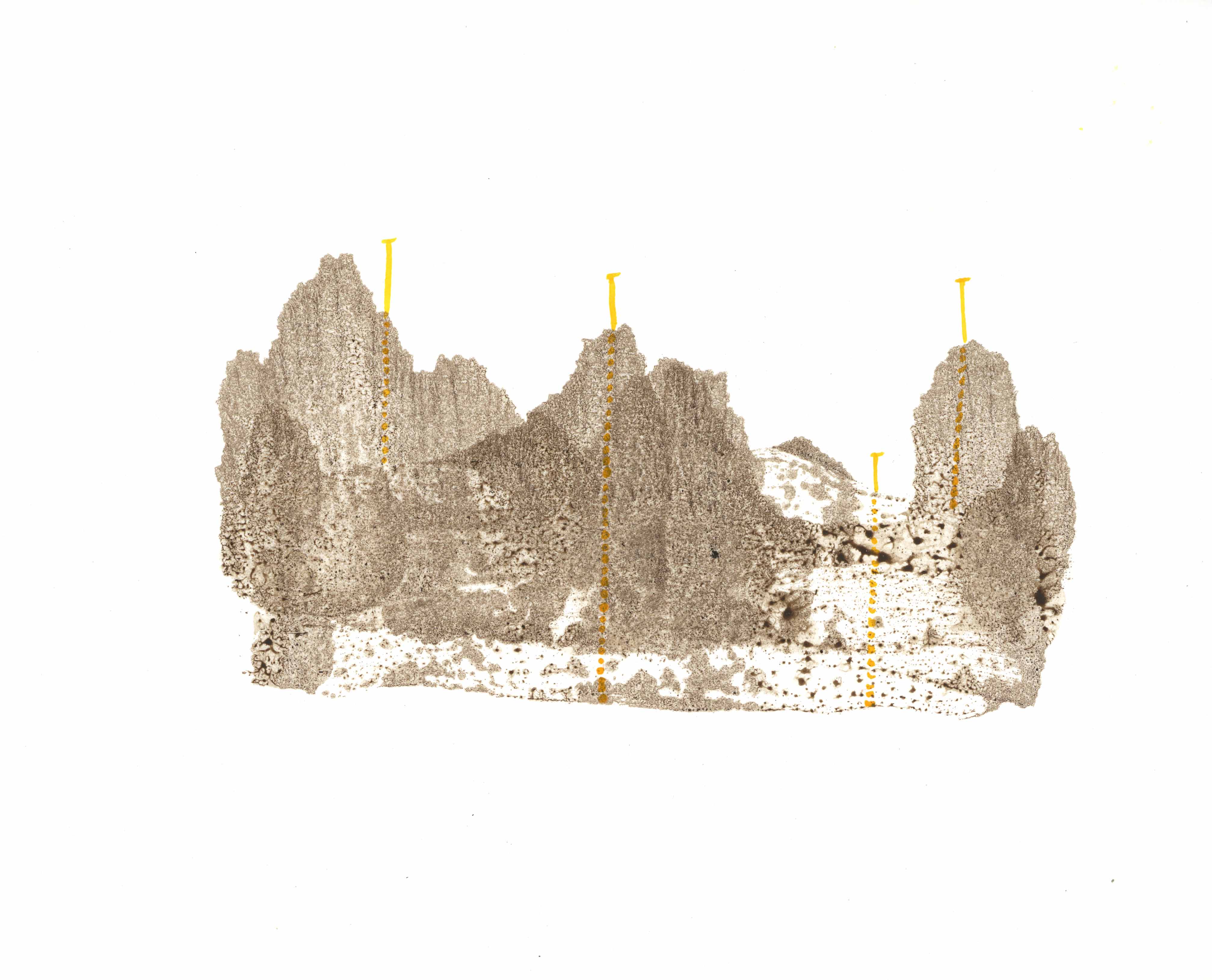

The drawing above was about how microtopographies indicate sites where carbon dioxide is invisibly moving into the atmosphere, reflecting on my dependence on science to envisage that this proces even happens.

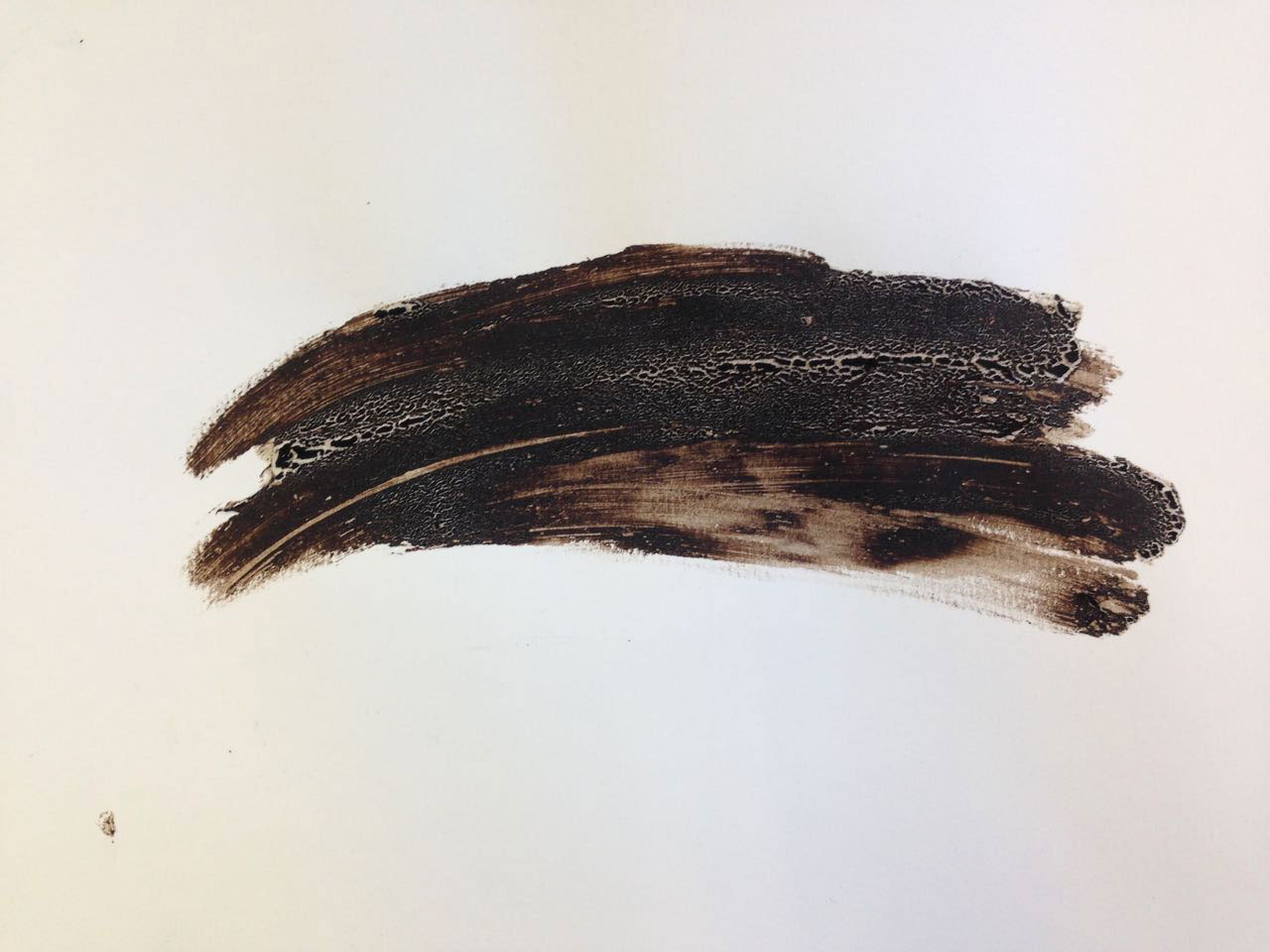

I began to use peat itself to make the marks. Thanks to Dr Emily Taylor, Rachel Coyle, and Drumclog Plant, I was able to recognise and collect a small sample of ‘Squagy’ peat – defined as ‘the perfect consistencey for a digger driver to make peat dams with’.

Working in the print room at Edinburgh College of Art let me explore peat as a material. It is easily dried and blown away, diluted and wshed away, and readily becomes friable – releasing carbon into the atmosphere as it goes.

This developed as a series of abstract prints reminiscent of landscapes.

How could I show these prints? Which way up should they go?

In the field, I had seen where Rachel Coyle (Peatland Action Project Officer at Tweed Forum) had measured the depth of peat in an upland area, surveying before restoration began at Crunklie Moss. I had this in mind, with this drawing on one of the peat prints. The peat probe used is typically orange.

Turned upside down, these prints might make you think about what is under your feet when you are on a raised bog. Given a restored green layer, and plenty of rain, the water table can rise and the bog be restored as a carbon store and habitat.

Peat seemed to convey the textures of a raised bog better than ink can, as I tested out with the prints below. Peat does its own thing well, especially when it’s wet with a living layer of sphagnum moss.

This post was prepared as an element of my project, Developing Peat Cultures.

More info: www.peatcultures.wordpress.com