In the uplands of the Scottish Borders, it’s mainly farming for sheep and trees – and now wind too. euroforest styles much of the landscape. (Not any company in particular – I use a small ‘e’ generically.)

I do not know who owns the patch next to where we live – but last Monday night ‘they’ started felling euroforest by floodlight. This week a cut is extending into a familiar view.

Last year we received a letter to reassure us that the contractors would be careful when they logged the section around our water supply. This year new work took us by surprise: Now the holes in the road out of the valley will now really go to pot! Hope the drivers look out for children, dogs, chickens.

So little I know. Who pays for the holes the lorries make? How much is a spruce worth? What is the wood good for?

I wanted to film the machine at work but it’s hard to actually speak to the operator to get permission. We wave at each other. I draw. I know nothing about these vehicles. I see them in animal terms: limbs, joints, mouths, and lots of erections. I think maybe the endbit is called a grapple-hook. It is very dextrous.

I wanted to film the machine at work but it’s hard to actually speak to the operator to get permission. We wave at each other. I draw. I know nothing about these vehicles. I see them in animal terms: limbs, joints, mouths, and lots of erections. I think maybe the endbit is called a grapple-hook. It is very dextrous.

A saw appears like a tongue after it grabs the trunk. It takes less than a minute to strip a tree and chop it. Last year I tried to hide from these scenes. This year I decided to learn about what happens. Seeing a tree fall is exciting. (I have read that artists in the Arctic cheered as huge blocks of ice fell from the bergs they watched, talking about climate change.)

A saw appears like a tongue after it grabs the trunk. It takes less than a minute to strip a tree and chop it. Last year I tried to hide from these scenes. This year I decided to learn about what happens. Seeing a tree fall is exciting. (I have read that artists in the Arctic cheered as huge blocks of ice fell from the bergs they watched, talking about climate change.)

Last year two girls ran along the leat which was to be cleared, shouting: “Run animals! Run!” What animals are there to run? Despite the dead space between closely packed spruce trees, we have seen squirrels, hare, foxes, deer, badgers, and crossbills (were they nesting yet?). Buzzards, pigeons, siskins, what do they do?

Last year two girls ran along the leat which was to be cleared, shouting: “Run animals! Run!” What animals are there to run? Despite the dead space between closely packed spruce trees, we have seen squirrels, hare, foxes, deer, badgers, and crossbills (were they nesting yet?). Buzzards, pigeons, siskins, what do they do?

Maybe the brush offers shelter, voles kept in view by a hovering kestrel. ‘Snags’ – dead standing trees – give vantage points for buzzards, crows.

Maybe the brush offers shelter, voles kept in view by a hovering kestrel. ‘Snags’ – dead standing trees – give vantage points for buzzards, crows.

One section of euroforest has been de-stumped. This seems crazy: it is rumoured to go to Lockerbie Biomass power plant. Renewable? However much oil does it take to dig stumps up and transport them? Elsewhere, ‘residues’ are scraped up. I wonder about dead wood decay into soil, about invertebrates? I am told dead wood adds methane to the atmosphere, acidifies the soil. What do I know? We see the soil run off in heavy rain.

One section of euroforest has been de-stumped. This seems crazy: it is rumoured to go to Lockerbie Biomass power plant. Renewable? However much oil does it take to dig stumps up and transport them? Elsewhere, ‘residues’ are scraped up. I wonder about dead wood decay into soil, about invertebrates? I am told dead wood adds methane to the atmosphere, acidifies the soil. What do I know? We see the soil run off in heavy rain.

euroforest is busy also in the Ettrick valley. On Monday residents’ anger will be aired at a public meeting. Broken promises, potholes, scarring access roads, abandoned sheep farms.

euroforest is busy also in the Ettrick valley. On Monday residents’ anger will be aired at a public meeting. Broken promises, potholes, scarring access roads, abandoned sheep farms.

Erasure of place upsets. We use words like ‘blanket’, ‘swathe’, ‘obliteration’, ‘monoculture’. There are traces of sheepscapes.

Erasure of place upsets. We use words like ‘blanket’, ‘swathe’, ‘obliteration’, ‘monoculture’. There are traces of sheepscapes.

With occasional trees older than a single human generation.

With occasional trees older than a single human generation.

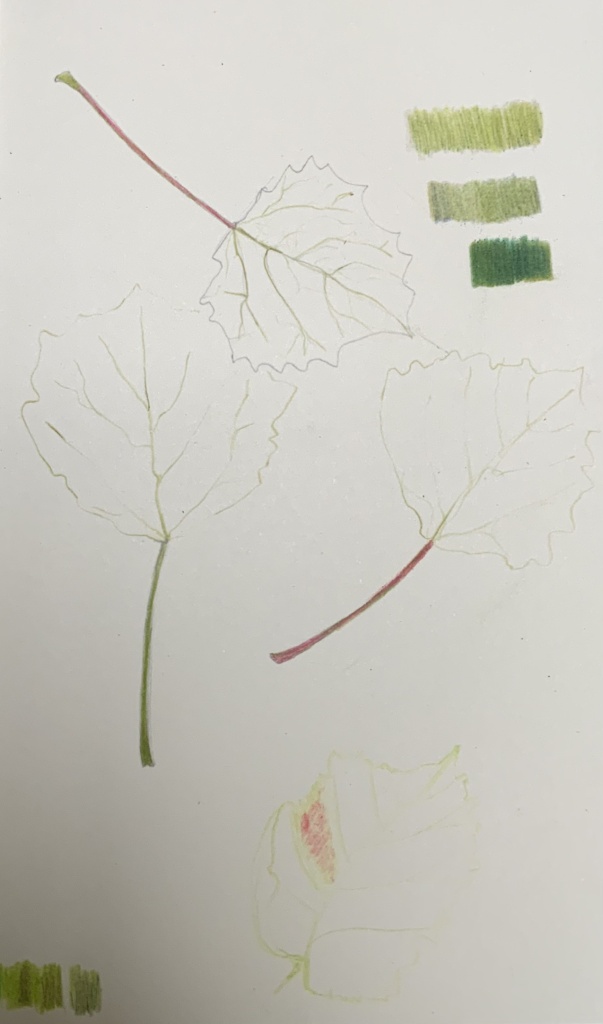

My proposal is to plant an aspen at upper Phawhope bothy at the head of Ettrick valley – as a Way installation inspired by the Forest Bookstore in Selkirk.

My proposal is to plant an aspen at upper Phawhope bothy at the head of Ettrick valley – as a Way installation inspired by the Forest Bookstore in Selkirk.

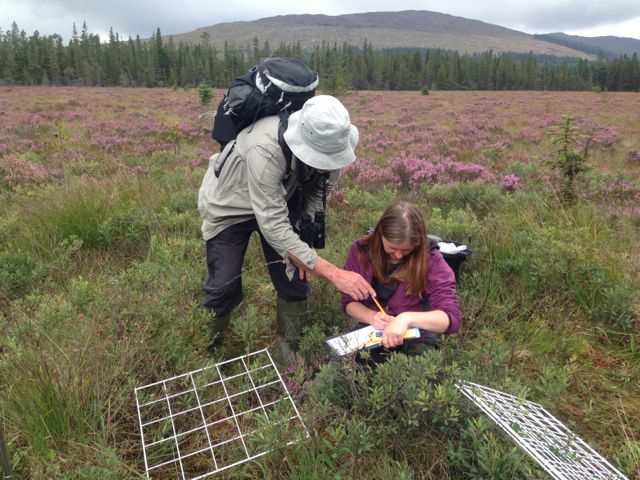

Endnote: This photo-essay is an introduction to my project ‘in the present tense‘ – fieldwork as an environmental artist about land use in the Scottish Borders. I look for entwined patterns of co-existence as animals, people, climate and land adjust to each other. I use drawing as a tool for investigation and this brings me into contact with people whose livelihood depends on the land. This highlights the resources of knowledge, skill and design underlying what may be seen as pastoral Borders’ scenery. This takes place within an industrial scenario where commodities are extracted. I think of my task as being to look carefully, scrutinise my own preconceptions and lack of knowledge, and draw out new connections. Borders’ farmland has been described as “sheep and trees, cows and ploughs”. I began with sheepscapes and am now moving onto trees. Tree-lines as a project started with the idea of deadwood and its generative possibilities – trying to ‘think like a tree’, prolong my anthropocentric time-line, and deepen my investigation to take in more about what is under my feet, and above my head.

Tree-lines offer a malleable idea for further investigation … land-use … climatic transition … life-lines and shelter … diagrammatic rendering (productivity, biomass, carbon sequestration) … pattern and repetition … supply lines … cultural entanglements …