Although it is a really bad idea for climate, peat is milled on an industrial scale in Scotland, and elsewhere.

“Coined “global coolers”[2], peatlands remove or “sequester” carbon from atmospheric carbon dioxide (CO2) and are known as “carbon sinks” or “pools”. Peatlands are thought to contain between 329 and 528 billion tonnes of carbon (equivalent to 1,200- 1,900 billion tonnes of carbon dioxide). Unless the bogs are disturbed by human activities, such as commercial peat extraction, much of this carbon can be stored for near geological time-scales [3]. ” Friends of the Earth Northern Ireland, report available here

Since the 1950s, gardeners have bought peat in large quantities.

So…private companies profit without paying for the environmental cost of releasing CO2. Meantime, some public money has been dedicated to restoring peatlands.

The way peat extraction releases carbon into the atmosphere is invisible unless you have developed an eye for carbon landscapes: seeing carbon in flux requires a new way of thinking.

As well as its ecological impact, peat extraction means the disappearance of an environmental archive; a previous post described the kind of information a peat core offers.

You can see signs of peat extraction on the A75, between Annan and Dumfries.

I stopped at a lay-by where you can see the Nutberry Moss works, with the old Chapelcross Power Station in the distance.

This is a place that is really only for those who work here.

You cannot get any closer to the diggings, even if you skirt round the smaller roads to the north. When I visited, the rifle range was in operation.

I am now curious about what happens here.

“The drains separate the peat mass into long ‘milling fields’, from which several thin layers of peat are then stripped during a year, amounting to around 200 mm per year. This bulk removal of the peat in the form of the industrial crop represents both loss of carbon and loss of the peat archive. The latter is lost forever because it recorded a particular set of moments in time which cannot be repeated. In the case of carbon, the net result of cutting and restoring a bog will be a loss of carbon compared to leaving the bog in its natural uncut state.” IUCN publication Source here

I wonder how much height Nutberry Moss has lost, and imagine a peat-core that could once have been taken here standing as a vertical pillar.

The scale of extraction at Nutberry is at a far remove from traditional peat digging.

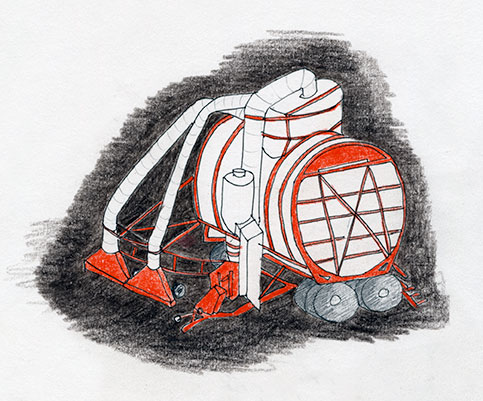

All the same, the machinery at Nutberry Moss is not nearly as massive as the Two-Head Vacuum Peat Harvesting Machine developed to get peat for fuel power stations in countries like Canada and Russia. This kind of machine hoovers up peat vastly more quickly than Sphagnum moss can ever generate it.

In 1999, a mysterious ancient object was found on Nutberry Moss. This two centimetre wide artefact is now in Dumfries Museum:

- “This ball has been decorated with coloured concentric rings of grey, red and green enamel or glass. It is probably Iron Age, although it was believed that enamel decoration like this was more characteristic of the Roman period. Archaeologists do not know what it was for. Carving such hard rock would have taken a long time. Perhaps it was a hereditary object, passed on from one generation to another, or maybe it was carried as a status symbol, or perhaps it was part of a game for which we will never know the rules.” Source: Future Museum

I lingered with this beautiful item, marvelling at its six faces and how its paint-marks survived sitting in a peat solution for centuries.

This Iron Age painted ball stayed in my mind as I returned past Nutberry Moss along the A75. I began to think of it as a seer’s eyeball, or a forebear of carbon’s helical symbol.

According to Janet Suzman, Primo Levi’s Periodic Table concerns the ‘essential matter of life that makes us, binds us, and with the detachment of the natural world, ignores us‘. Levi’s story of a carbon atom allows it to escape from being bound up in bedrock for hundreds of millions of years, to become the energy giving him capacity to impress, on paper, the dot at the end of his story.

With thanks to those who have helped me start to see carbon landscapes, Dumfries Museum, and Michael van Beinum.

One thought on “a blind eye”